Closing the Circle:

The Life of Tzila Zakheim

by Amy Cohn

Foreword

Each and every account that we read or hear about survivors during the holocaust years is heartrending. It is hard to conceive what these heroes endured during that period. My mother, Tzila Zakheim (nee Kopelowicz) and Sonia and Ignat Yemelovitch are, to me, some of those heroes

During her visit to Israel in the winter of 2008, I was showing my husband's niece, Amy Cohn, then a 15 year old school girl from Sydney, Australia, the album I compiled about my mother's life in her beloved shtetl Mir, from the war years and until her death in 2003. When Amy first met "Bobba Tzila" in Israel, she was a little girl. Over the years she had heard the family talking about her war experiences and after seeing this album felt the need to pay tribute to "Bobba Tzila". The result is this remarkable essay on "The Life of Tzila Zakheim". This essay is a tribute to three heroic people; my mother Tzila Zakheim, Ignat and Sonia Yemolovich and to the people of the shtetl Mir who were murdered during those awful years of the Holocaust.

Eileen Fridman

Efrat, Israel

February 2011

|

Honoring the memory of Tzila (Kopelowicz) Zakheim

(1922 – 2003) |

|

Tzila Zakheim, was born to Israel Chanan and Etel Kopelowicz, in Mir in present day Belarus, on the 15th September 1922. Her father Israel Chanan Kopelowicz had been married before and had six children from his first marriage. Tzila had one brother from her parent’s marriage. Tzila’s siblings from her father’s first marriage were quite a lot older than she was. Like many of the Jews in Mir she spoke Yiddish in the home and Byelorussian outside her home. Tzila attended a government school from age six and got on well with the Polish and Russian children. In addition to her government secular schooling, Tzila, along with the other Jewish students, attended Talmud Torah to learn Hebrew.

Mir, located 120 kilometres from Minsk, was a small town with approximately 3000 Jews at the start of World War 2. The Mir Yeshiva was renowned worldwide and young men came from not only Lithuania but from as far afield as Australia, South Africa, the United States and England to study there.

|

Many of the town’s people made a living by providing board and lodging to the Yeshiva bochers. The Yeshiva and its students managed to escape the German invasion with the help of Sugihara, the Japanese Consul from Kovno. He granted 300 visas to the students after the Germans invaded Poland and then Lithuania. All in all, Sugihara granted over 2000 transit visas to the Jews of Kovno and the surrounds. The Yeshiva first relocated to Kobe in Japan, but after Japan entered the war they were deported to Shanghai, where they remained until the end of the war. Today there are two branches of the Mir Yeshiva; one located in Jerusalem and one in Brooklyn, New York.

The Jewish community of Mir, influenced by the Yeshiva, was an orthodox community, as was Tzila’s family. They observed Shabbat and all the Yom Tovim. Although Tzila’s family went to shule regularly on a Shabbat, she only went on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. The people of Mir were also very Zionistic and like many of the Jewish Youth, she belonged to a Jewish Youth Movement, Hashomer Hatzair. Hashomer Hatzair played a significant role in many young Jews’ lives. Through the Youth Movement they were able to participate in “Kibbutz” programs where they could learn skills in farming so that they would be awarded with papers to go to Palestine.

Tzila’s family lived at 52 Zavalna Street in Mir. Their immediate neighbours were Jews, though there were gentiles living in her street. Tzila and her family were fortunate that Jews and gentiles got on well together prior to the Second World War; in many Polish and Belarus towns and settlements anti-Semitism was already on the rise. Tzila’s half brothers and sisters chose to leave Mir and settle in South Africa and South America, leaving well before the German invasion of Mir. Pesha Dobrin, Feigel Kramer, Morris Kay and Alec (Eliahu) Kay all went to South Africa and settled in Johannesburg. Faivel (Phillip) Kopelowicz settled in Buenos Aires in Argentina.

When Tzila’s mother fell ill and died, just after Tzila had finished school, the absence of older sisters was felt as Tzila was forced to take up the mother role and take care of every one. As she used to say, she became the “Ballabusta” . This was a huge responsibility as life in Mir was very difficult. In winter the harsh climate provided a lot of obstacles that needed to be overcome in order to continue with day-to-day life. To combat the cold a fire needed to be constantly burning and that took a lot of work. In order to keep the fire burning there needed to be a continuous supply of wood that had to be chopped by hand. Tzila remembered that it was especially difficult to make a fire when the wood was wet; “When the wood was wet you would get a headache and you would want a cup of tea, but you need to chop the wood and put it on the fire and bring a bucket of water and put a pot of water over the fire until the water is boiled and by then you don’t want a cup of tea anymore.”

|

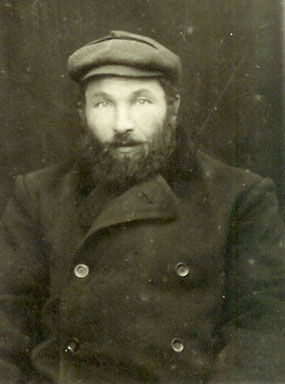

Tzila’s father, Israel Chanan Kopelowicz,

was killed in the ‘last shechitah’.

|

Tzila with her younger brother, Mendel, who was killed in the ‘first shechitah’ in November 1941.

|

Tzila with her older brother Michael.

Michael and his wife were killed

in the forests outside Mir.

|

The community of Mir first heard of the Nazi’s rise to power in 1932 when Hitler came to power. They would listen to the news on the Radio and read about it in their own Yiddish Newspapers. People were worried but felt that they couldn’t do anything. Tzila’s father had no intention of leaving Mir even after he heard of the problems. He felt that he was too old to travel or to move. In those days sixty was already considered old.

The Nazi’s arrived in Mir on the Friday the 27th of June 1941. Tzila remembers the Germans marching and singing "Deutsch Dimeralus", meaning “Land Dive” and crying “Das is Hasbliskri”. The war is very quick. Tzila remembers being at home when the German’s came and that she didn’t attempt to hide.

All the changes that were made in Mir were notified to the Jews on placards. They included:

Jews must not live with non-Jews.

Jews must wear a white band on their left arm with a yellow Magen David.

Jews are not allowed to walk on the pavement.

Gentiles would walk with a stick and scream “Yud Kaput” meaning “Jew is finished” if they saw a Jew on the street. This was the first time there had been unrest between the Jews and the Gentiles in Mir.

After a few weeks the white band was not enough. Jews were told to wear a yellow badge on the left front and right back. Then after a few months that too was not enough and the Jews were told to make a Magen David to wear on the front and back so that people knew that it was a Jew walking in the street. Jews were often chased to work, to clean the streets and houses of the police and Germans. This went on from the 27th of June 1941 when the Germans arrived, until November that year.

Soon after the arrival of the Germans in Mir, the town started to go up in flames. Tzila was unsure as to how the fire started but half the town was burnt down. Her house was fortunately saved and the family welcomed neighbours into their house to live with them. People slept on the floor and they took doors off their hinges and used them as a base to sleep on. Tzila, herself, shared her bed with three other girls.

During a Shabbat in August 1941 they got wind of news that more Germans and police had arrived in Mir. People had a foreboding feeling that something worse was coming. The Germans had already begun lying to the Judenrat, (a council of Jewish elders forced to carry out the Germans orders):

“We need the Jews for work,” and “We are not going to kill the Jews.” The Jews had already heard from their Gentile neighbours that in other towns the Jews had been killed. It was on the Shabbat of the 19th of Cheshvan, corresponding to the 9th of November 1941 on the Gregorian calendar, that the Germans decided to annihilate the Jews of Mir.

Tzila remembered that it was still dark when they first heard the shooting. She dressed quickly, as she had already heard the Germans chasing the Gentiles to dig graves with shovels; the police had already been to their houses. Tzila ran by herself to a non-Jewish family, Ignat and Sonya Yemolovitch, who lived on her street and with whom she was friendly. She didn’t know where her family was, because there was such a lot of noise and panic in the house when the police came to chase them out. Sonya told Tzila to go to the stable; she must not remain in the house. Already hiding in the stables were (1) two young boys, a mother and daughter and another woman who managed to stumble into the stable. She remembered hearing the killing and shooting from the stable. The Germans came to inspect the stable and even looked through the straw where Tzila and the others were hiding, but they were not discovered. Ignat knew of Tzila’s presence in the stable from his wife Sonya, but he did not know the others were there. Many other Jews who were hiding were found and those found were sent to their graves. This massacre came to be known as the “FIRST SHECHITAH”. Tzila’s younger brother Menachem, who was only 13 at the time, was killed running in the street.

The shooting continued from morning until four o’clock in the afternoon. Once the shooting had ended, Ignat returned to the stable and called out for Tzila. He did not know of the presence of the others. Tzila was scared to answer him but eventually Ignat looked through the straw a little more thoroughly than the Germans had done and found Tzila and the others. Tzila started crying but Ignat reassured her and told her that he was going to bring them food. His wife Sonya was making latkes. It was already night and all of them were to stay there for the night.

Ignat went into town to see what was happening. He went to Tzila’s house and met her father and one brother. He learnt that Tzila’s younger brother, Menachem, had been killed in the shooting. He explained to her father that Tzila was with them, but that she would not return until the following night because it was not safe for her to walk in the town now. Ignat was also scared for himself and Sonya; people mustn’t see that there were Jews leaving his stable. Ignat and Sonya Yemolovitch would later play a vital role in saving and protecting Tzila. Tzila and the boys returned home to hear the stories the following day. People were crying, “In the streets they kill, people were running and they were killed.” The dead were buried in two big graves on the side of the town. Two thousand five hundred Jews were killed on that day out of a total Jewish population of just over three thousand. Only 850 Jews now were left in Mir.

Around the time of the first massacre a German officer by the name of Oswald Rufeisen (2) was employed by the Commandant Serafanowics to act as an interpreter. The Jews considered him a “good” policeman. Oswald Rufeisen was in fact a Jewish man who by a stroke of luck was able to find German papers that matched his physical description at the start of the war. He was born Shmuel Rufeisin and originally came from a small village near Oswiecim in Poland. As the Nazi’s advanced, Shmuel and his brother Arieh moved from place to place trying to escape them. They spent some time in Vilna until the Germans invaded Lithuania. When Shmuel escaped from Vilna he found a package with papers belonging to a German man. He realized that they looked alike and he was able to pass himself off as an Aryan German. He was also able to speak Polish and German fluently. He changed his name to Oswald Rufeisen, Shmuel being too typically Jewish, and he was able to get himself a job as an interpreter to the German Commander of Mir, Semion Serafanowics.

At the beginning of the winter of 1941 the Jews were chased into a ghetto. The ghetto was located in the Mirski Palace; it was called Zomick in Polish and Russian and Shloshes in Yiddish. The ghetto was heavily over crowded. Rufeisen was able to have easier contact with his Jewish comrades, and helping them plan an escape became easier. The Germans gave all their orders through the Judenrat. They continued living in the Ghetto through the following summer, their only refuge being that they were allowed to work for people outside of the Ghetto, but their wages were to be paid to the Nazis. Tzila was fortunate that Ignat and Sonya Yemolovitch came to her salvation again and she was hired to work in their fields. Her position with the Yemolovitchs proved to be very valuable, as not only did it allow her to leave the Ghetto but they treated her well and provided her with food; Tzila only ate what they provided her with. She worked hard during this time, from early morning until five or six in the evening. On one occasion, while he was paying Tzila’s salary to the Nazis, the Germans asked Ignat if he thought Tzila was preparing an attempt to escape the Ghetto. After his silence the Germans reminded him that if he should ever know anything he would be obliged to notify them. Ignat returned home and recounted the event to both Sonya and Tzila and stated that if he ever heard anything he would tell her himself to try and run away. Tzila remained working for the Yemolovitchs until she ran out of the Ghetto.

|

Oswald Rufeisen began helping the Jews in the Ghetto. He recognized one of the Jews, Berl Resnik, as someone he had met in Cracow at a Zionist movement and was able to convince him as to who he really was. He supplied arms and trained a small group of young men in unarmed combat. The group included Mike Breslin who later settled in South Africa. He also passed on vital information about what the Germans intended doing with the Jews of Mir. One day in August 1942, Oswald overheard the Commandant telling someone that the Ghetto was going to be annihilated. Armed with this information, he arranged to leave the Gate open on the 9th August for the Jews to escape and got word to the Jews that he had done this through Mike Breslin. He also arranged for the Nazis to go to the forests to look for Russian partisans. Two hundred people managed to escape. Some were too old to go, others too afraid. Tzila’s father told her and her brother to leave. He was too old to run away and hide in the forests. One young girl was worried about not having an eiderdown or cushion in the forests. Tzila’s father said to her “she’s talking nonsense. Here we are getting killed. You must run out. Maybe you will save your life. It is no use to sit here. Don’t think about the cushion”. This was the last time that she saw her father.

|

Castle window used for escape |

Even though the gate of the ghetto was open, Tzila and other boys and girls jumped out a window in a desperate attempt to escape, as they were too scared to use the gate. Tzila remembers the panic surrounding them was terrible. Some people knew of Oswald’s true identity and knew that he had taken the guards with him, but there was still fear that there were guards around the castle and that they were walking into an ambush. It was dark when they left the castle and Tzila wanted to go to some people she knew in the villages next to the forest, knowing that from there it would be easy to make her way into the apparent safety of the forest. Tzila ran the whole night but as it got lighter she could see that she was on the other side of town and that she had completely lost her way. They had run out of the Ghetto on Sunday night and by then it was Monday; Tzila lay in the fields all day Monday and remained there until Wednesday night by which time she had summoned the courage to leave the fields and walk through the streets of Mir to the Yemalovitchs. Since leaving the ghetto on Sunday night Tzila had not eaten. Ignat told her to hide in his field. She knew his fields very well by that stage as she had spent close to a year working there. Though he didn’t tell her, Tzila knew that Ignat was scared to keep her on his property. Tzila didn’t realise but a neighbour had seen her running. It was nearly daytime, but he didn’t attempt to catch her. It was eight or nine o’clock in the morning when Tzila heard the shooting coming from inside the ghetto. They were killing the Jews who were still trying to run away. |

She heard people crying out “Shema Yisroel” as they were being shot. It was then that Tzila made the decision that if she was still alive by nighttime she would run away from Mir. She was confident that she knew the way to the forest. She heard Sonya calling her but was afraid to answer and so remained silent. When Ignat arrived home that night Sonya told him that she was afraid that Tzila had been shot. Ignat went to look for her. He found her and Tzila started crying. She was afraid he would turn her in. Tzila remembered him telling her “don’t worry I won’t kill you.” He held onto the jar of water that she was drinking as she was drinking it too fast. He tried to give her bread but her gums were too sore to eat. At the sight of Tzila struggling to eat a piece of bread, Ignat started crying. He went home and got Sonya to make her latkes and brought them back to her in the field. When it was dark they took her back to their house. Tzila had left the ghetto in a white skirt, but by this time her skirt had turned a deep grey and so Sonya gave Tzila more suitable clothes and food to take with her. Ignat led her to the end of his fields; from there she knew how to make her way into the forests. The only thing they couldn’t give Tzila that night was a pair of shoes, Tzila didn’t have proper boots for the forest. The only way they had of giving Tzila more suitable shoes was for Tzila to return to Mir in three weeks time and by then Sonya would have boots made for her. Exactly three weeks later Tzila returned to their home in the middle of the night. Shaking, she knocked on their window. They let her in the door and they sat all night talking; the whole town was scared they told her. Tzila was unable to leave them that night as by the time she was ready to leave it was almost day, so Tzila stayed in the stables all of that day and when night came Sonya gave her food, as well as the boots, to take with her to the forests and once again Ignat took her to the end of his fields and Tzila ran into the forest.

It was summer when Tzila first entered the forest. She had been in the forest on her own for most of the time. At first she and three girls slept on the ground and then in a bidel (hut). Intermittently Tzila would return to her friends, Sonya and Ignat, and they would give her bread and milk; Tzila and the girls ate once a day. In the winter of 1943 they slept in a zublanker (bunker). Sometimes there could be ten or more people. One night while she was visiting Sonya and Ignat they heard shooting in the distance. Ignat told her it was too dangerous to go back to the forest. She hid in the barn until the next night. When she returned to her camp she found that they had all been shot and killed, including her brother Michel and his family.

|

Official partisan commands were known in Russian. In 1943, soon after her brother had been killed, Tzila decided to join the Tuvia Bielski’s Otriad, although it was 40 km from Mir. There were many other otriads in the forest, many made up of Russian and Polish Partisans, but they were not keen to accept Jews into their group as they created a greater threat for themselves. Some Jewish males were able to join these otriads due to their prowess in fighting or they had arms to supply; women were not even considered as they were regarded as burdens. If a Jewish girl were attached to a gentile in the otriad they would sometimes provide for her and accept her into the otriad on the condition that she remained with the gentile. People with arms were accepted much more easily into groups. Most Otriads wouldn’t even consider a Jew, or would kill any Jew that approached them. Having a gun helped Jews get into a position of better safety. Tuvia Beilski was unique in that he accepted any Jew into his otriad, believing that every person had the right to life and to survive and that the best sort of resistance the Jews could possibly have would be to survive. It had become too dangerous to go to the villages, so Tzila had stopped going to Sonya and Ignat. It therefore did not matter if she was far from Mir. There were over 1000 people living in with the Bielski camp.

The Bielski camp was very well organised with many facilities of a small village, even if they were rudimentary. There was a bathhouse, mill, bakery, kitchen, medical clinic and quarantine hut for those people with infectious diseases. They even had a herd of cows. The camp eventually became so developed that they were able to set up workshops in which they would make shoes, clothes and other items that were considered luxuries at the time. These items provided the Otriad with a means to support themselves and made them useful for the Russians, thus furthering their own safety and the protection by the Russians. For the few children that had survived in the forests, a school was created and they would learn. Often the children would rehearse plays and skits not only for their own enjoyment but for the enjoyment of the other members of the Otriad.

The conditions of the forest camp, while better than what could have been expected, were still much lower than what people had been used to. The people slept in dugouts and mattresses were made of anything one could get hold of. The supplies that belonged to the whole Otriad went into the workshops. Tzila was fortunate to have worked in the bathhouse, which even had hot water. Because of this position she was able to have a bath every day. Most other people were only able to bath once a week. They got soup and bread everyday where possible, but the amount you got depended on your place in the hierarchy. If you were part of Tuvia Bielski’s personal group your portions of food would be much greater and anything special that was delivered to the cook would be served to you. Another benefit of working in the bath house was that Tzila was given extra portions of food. If you worked or were a fighter the food portions allocated to you would be greater.

It felt safer in a large group compared to the smaller groups she had lived with previously. There was fighting all around them but they were safe in the forest. Most of the people in the Bielski camp were young. They even had a shochet in the camp. They knew when the Jewish holidays were and tried to keep them. Tzila remembers people attempting to kosher their few utensils on Pesach and at first not understanding why. Only after asking them why they were koshering utensils that would later be used on food that had been taken from something that wasn’t koshered did she understand. One lady started crying as she explained, “we used to kosher for Pesach,” it was the only thing that they could do to acknowledge the chag. During their time in the forest they sat around and sang a lot. In the evening and when they didn’t have food they sang a lot. “When a person is hungry your voice is very clear.” It was fortunate that in those conditions very few of the people became sick. While living in the forests the Jews were not only scared of the Germans, but of the Russian and Polish Partisans who often also attacked and killed Jews. The Russian threat became less as the Jews became able to supply them with resources; the Bielski Otriad was the only camp that was able to manufacture leather goods.

|

She stayed with the Bielski’s until the 22nd June 1944 when the Russians liberated the area. Tzila remembers the Russian Major saying “we are already on a big free earth; you are all free already.” The Russians didn’t have any spare food to give them, for they still had to go on to Poland. All 1,230 members of the Bielski group emerged from the forests together and walked for a few days until they marched in to Nowogradek, the nearest town, together. The survivors were mainly young; the old people weren’t able to endure the harsh conditions.

Once they had reached Nowogradek they all decided to return to their original homes and attempt to reclaim ownership. Tzila and three other people managed to get a ride with a Red army lorry on its way to Minsk. When they saw Mir they were horrified. The town had been burnt and destroyed with only the Church buildings remaining. They all cried. Tzila made a quick decision that if her house had been destroyed she wouldn’t remain in Mir but to her delight it was fine. When they were forced into the Ghetto Tzila’s father had asked a gentile to live in the house and look after it for them. She was living there when Tzila returned and had invited many other people to live with her. Tzila was frightened when she walked into the house and saw all those people there; the threat to Jews was not completely gone. The gentile attempted to keep Tzila there as she explained to the others that Tzila was the rightful owner of the property but Tzila, in her fright, ran. She decided to find Sonya and Sonya and Ignat took her in. Sonya told her about how the neighbour had not reported her when he saw her running in their field. It was on Sonya’s suggestion that they decided to throw a party for him. Tzila felt bad that she could not afford to throw the party but once again Sonya’s overwhelming generosity prevailed and she provided everything necessary. When he entered and kissed Tzila hello, Tzila said to him that it was “a good thing you didn’t catch me.” He replied “Catch you and give you to the Germans. I could never do that”. After the party the woman who was looking after Tzila’s house arrived at the Yemolovitch’s home to ask Tzila to come back to her house and there she would share a room with her daughter who was the same age as Tzila. On Sonya’s advice she did this, although she spent most of her days with Sonya. The woman provided Tzila with a bed, a cushion and an eiderdown, all the things that the young girl had been afraid of losing if she attempted to escape the ghetto.

|

That July, Tzila got a job working in a shop; the Government insisted that the Jews find themselves an occupation. The Jews in Mir were very fortunate as there was not much anti-Semitism and Tzila was treated well by the gentiles. Jews in other towns and villages had to flee as they were at risk of being killed by the local population and many people were unable to reclaim their houses that had been occupied by gentiles for the duration of the war. In February 1945, Mike Breslin returned to Mir. He told Tzila that the war was nearly finished and that they would all have to leave Mir. He advised her to sell her house for Russian Gold, and advised that she should not accept Russian Roubles, and that she should use the money to buy clothes and pay for transport to get her to the West. Sonya and Ignat helped her sell her house for 120 Russian Roubles in gold. Ignat even collected the money for her as it was too dangerous for her to do so.

The war ended on the 8th May 1945. Tzila was not ready to leave. She was still working and had to pack up. She, together with Kunye and Sarah Kagan from Mir, left in July 1945. She wanted to give Sonya and Ignat ten Rouble but they wouldn’t take it as they knew Tzila’s need was greater than theirs. Tzila and the Kagans left by train for Poland. They were too afraid to go to Bialystok as anti-Semitism was rampant there and Poles were shooting Jews. They couldn’t go to Warsaw as the whole city had been bombed and they wouldn’t have had anywhere to stay. They elected to go to Lodz. Because of the anti-Semitism in Poland they didn’t speak Yiddish in the streets; if you were caught speaking Yiddish you could be killed. They were able to find accommodation and met up with other Jews who had survived the war. It was in these sorts of instances that Jews would warn each other about leaving Poland out of fear of the Pogroms.

|

Because of the anti-Semitism Tzila, together with a large group of survivors, decided to go to Czechoslovakia. They were all mainly young people. They did not have passports or any sort of travel documents or train tickets. At the border the boys in her group bought the police Vodka and they let them through. When the train officers came looking for tickets the whole group jumped off the train. They then had to walk to Prague where they were met by The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (The Joint). Thinking back Tzila knew that something like that can only be done when you are young; the old could never have done what she did. “The Joint” put them up in a hotel. When they woke up the next morning they were covered in lice. After giving them a bath and burning and replacing their clothes they were moved to another hotel. She stayed in Prague for a month. She was in Prague over Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur and remembered going to a most beautiful Shule and for the first time in years she voluntarily fasted on Yom Kippur. From Prague they had to get to the Munich, which was in the American Zone. They again took a train but still did not have passports so that when they got to the border they jumped off the train, slipped across the border and walked to Munich.

On their arrival in Munich the group was once again taken in by the “Joint”. Tzila remembers how refreshing it was to hear people speaking Yiddish like “our people”. The “Joint” supplied them with food but soon warned them that Munich was not a safe place for them to remain long term. They were provided with trucks that they would then drive to Landsberg Am Lech. In Landsberg Displaced Persons, which was one of the largest Displaced Persons Camps in Europe, they were all given shared housing. Tzila laughed as she remembered falling asleep on the first night, before they were given decent housing. She was sharing a double bed with a couple of other people and it broke in the middle of the night. The next morning they were all taken to nice places where many of them would stay for a long time. The “Joint” supplied them with food for one week and Tzila recalls eating the whole amount in one meal.

|

|

Mir friend Sarah Kagan (on right)

|

Photos of more friends from Landsberg Camp

|

|

|

|

Tzila remained at the Landsberg Displaced Persons Camp until she left for South Africa in July of 1947. She had intended going to Palestine, but the Red Cross, with the help of Mike Breslin, were able to trace her siblings who were living in South Africa.

|

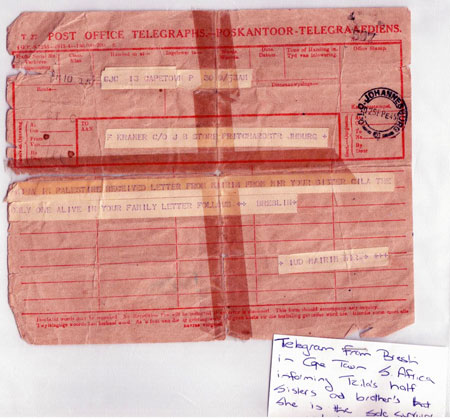

Mike Breslin, who had seen Tzila in Mir, sent a telegram to his brother Kiva (Akiva) in Israel who sent a telegram to his brother Binyomin in Cape Town who sent the telegram to Tzila’s sister, Feigel Kramer, in Johannesburg who in turn managed to coordinate with the “Joint” so that Tzila could travel to South Africa.

With the help of the “Joint” she went to Paris. From there she was sent to London. She was told to wear a white bandage on her right arm when she reached London but was not told that it was to be used for identification purposes. Because she didn’t understand why she had to put on the white bandage she didn’t put it on, and was left stranded at the station. She eventually found a policeman who was just about to go off duty, and in broken English managed to convey to him that she was lost. He took pity on her and after showing her around London took her home with him where she spent the night with his family. The next morning he took her to the police station where they contacted ‘The Joint’. They picked her up and explained that they were looking for someone wearing a white bandage. She stayed in a boarding house in Gower Street until she departed for South Africa. |

Telegram that Tzila's half sister Feige, in South Africa,

received from Eliezer Breslin notifying her

that Tzila was the only person alive in her family.

|

The journey to Johannesburg took two days on an aeroplane called a Skymaster, landing every couple of hours along the route. She was met by her family and went to live with her half sister and brother-in-law, Feigel and Chonie Kramer. On her arrival in South Africa the spelling of her name changed, the South African’s started spelling it Cyla so on different documentation the spelling is different.

|

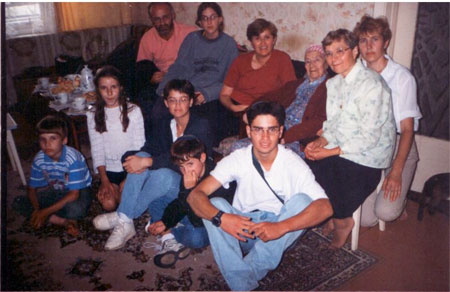

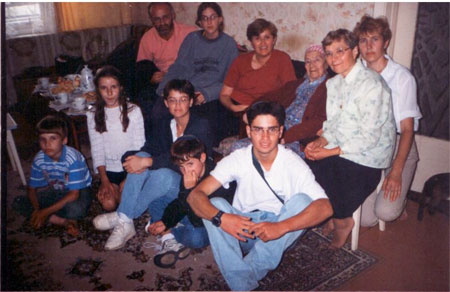

Tzila with her family in South Africa shortly after her arrival |

Tzila in South Africa |

In South Africa, soon after her arrival, Tzila met Chaim Zakheim. They were married in 1948.

|

Tzila and Chaim Zakheim in 1947 in Johannesburg, SA |

Chaim Zakheim and his family had managed to leave Lithuania in 1938. His father had passed away, so his mother lived with them from the time they were married.

They originally lived in a house in Bertrams in Johannesburg until 1956 and then in a house in Bezuidenhout Valley. Tzila helped Chaim in his shop every Friday and Saturday. They had three children: Chonie (Israel Chanan), born in 1949, Ethel, born in 1952, and Eileen, born in 1954. Chaim and Tzila were determined to ensure that their children retained their Jewish roots. They all went to King David School, the Jewish Day School in Johannesburg and spoke Yiddish at home. Tzila and Chaim had both learnt to speak English but wanted their children to carry on their heritage.

|

Chonie recalls “We were all brought up with the knowledge that our mother spent nearly twenty months in the forests of Poland because she had been threatened and that the people who were threatening her were not only Germans but also people who lived in her village. From a young age we were told most of the stories of the beginning of her life and slowly over the years as things developed more and more came to light… For myself, personally it is something still very difficult to get to grips with that your neighbours and people who knew you should suddenly turn upon you.”

Mike Breslin and his brother Eliezer Breslin, who was second in command of the Judenrat in Mir, often visited Tzila in Johannesburg. Tzila had another friend Yente Glekel who had also come from Mir and had survived the holocaust. She, too, lived in Johannesburg and Tzila would meet her once a week for coffee and together with Chaim, she would visit her and her husband every Sunday night.

|

Zakheim Family |

Although Tzila had known of the part Oswald Rufeisen played in saving her life she had not met him. Through Mike Breslin she knew that he had survived the war and had converted to Catholicism. So it was with great interest that she followed the trial of ‘Who is a Jew’ that was being heard by the Israeli Supreme Court. An article appeared in the 7th December 1962 edition of Time Magazine headlined ‘ THE DEFINITION OF A JEW’. It reported that Father Daniel from the Carmelite Order was petitioning to become a citizen of Israel under the Law of Return. The High Court of Israel was sitting to hear this case. He said that “My religion is Catholic but my ethnic origin is always and will be Jewish. If I am not a Jew then what am I? I did not accept Christianity to leave my people. It added to my Judaism. I feel as a Jew.” This article referred to Oswald Rufeisen. She then learnt about what happened to him after he had saved as many Jews as he could in Mir. The Commandant had become suspicious of him and he was locked up, ready for execution. He was able to escape through a window and took refuge in a monastery at the edge of Mir. When it became too dangerous for him to live in the Monastery he too joined a group of partisans in the woods, but not the Bielski Otriad. Mike Breslin saw him in the forests in the winter of 1944. After liberation he returned to Mir with the other survivors, but one day he disappeared. After Mike Breslin settled in South Africa he heard that Oswald had been seen in Cracow. dressed like a monk. While he was living in the monastery he read up on Catholicism and he decided that after the war he would convert. However, he still wanted to live in Palestine because he was a Zionist and because his brother Arieh had managed to get there before the war. In 1949 while on a visit to Israel for a reunion of survivors Mike Breslin saw Oswald at the Carmelite Monastery in Haifa. After the war he had converted and after the State of Israel was established he applied to go to live there under the Law of Return. The High Court denied him the right to live in Israel under the Law of Return, but he was granted Israeli citizenship and he went to live in Haifa at the Carmelite Monastery.

|

Tzila kept in constant contact with Ignat and Sonya after she left Mir. Once she reached South Africa she started sending them food parcels. Then all of a sudden in 1963 they stopped corresponding with her. She was very upset but did not know what to do. She had no means of looking for them as the South African Government had no diplomatic relations with “The Soviet Union”.

In 1968 Tzila and Chaim went on holiday to Israel and Tzila had a very emotional reunion with her friends from Mir and the Bielski Otriad. Her reunion with Kunya Kagan was especially poignant.

|

Friends from Mir in Israel

|

Tzila and Chaim had 3 children, Chonie, Ethel and Eileen and 12 grandchildren.

Chaim Zakheim passed away in 1983. Tzila sold the house. Her mother- in-law, who was still living with them at the time of Chaim’s death, went to live in the Jewish Old Aged Home, “Sandringham Gardens”. Tzila went to live in a flat in Yeoville in Johannesburg. Tzila travelled up and down to Israel on a regular basis to visit her daughter Eileen and her son Chonie and their families. During this time she suffered from hernias and had to be operated on several times. All the operations were successful and did not stop her from continuing her travels.

|

In 1986 her daughter Eileen decided to contact Father Daniel in Haifa and tell him who she was and thank him for saving her mother’s life. Eileen and her family had settled in Efrat, in the Gush Etzion block. One day, in 1986, her son Dan came running to her to say that Father Daniel was looking for her. He had arrived at the small shop Eileen owned and ran. They had a very emotional meeting.

|

In 1987, while on a visit to Israel, Tzila and Father Daniel had a very emotional meeting. From then on they kept in contact. Father Daniel was someone Tzila held close to her heart as she considered him one of the people responsible for saving her life.

In 1992 Tzila received a telephone call from Scotland Yard to say that they had arrested Simeon Serafanowics, who had been the Byelorussian Commander of police in Mir during the German Occupation, for war crimes.

She was asked to testify. Two Scotland Yard detectives flew out to South Africa and interviewed her for two days. Tzila found this a very emotional and difficult process. She was being asked to recall and remember events and people accurately after 50 years. She found it hard to identify the photo of the old man he had become with the person she remembered from her youth. |

Tzila with Father Daniel (Oswald Rufeisin)

during their first reunion in 1987 |

Eileen speaking at the mass grave

where Tzila's younger brother Mendel

and many others were killed.

Mir Survivors at the mass graves in Mir on their trip in 1992

Mir Survivors at the mass graves in Mir on their trip in 1992 |

Another event, also of great significance to Tzila also occurred in 1992. Israel Shifron, Chairman of the Mir Association in Israel, organized a trip to Mir for all the survivors and their descendants. Father Daniel accompanied this group. One of the main aims of the trip was to lay tombstones on the places that Jews had been massacred. Because of her ill health Tzila was not able to go but her daughter Eileen went in her place. Eileen found this to be a very emotional experience.

Afterwards she spoke of her trip, “we grew up with our mother’s past… for me we had closed the circle.” She found her mother’s old house; it looked exactly as her mother had described it to be. When many of the neighbours heard that Tzila Kopolewicz’s daughter had come to Mir they were very excited, all wanting to know how Tzila was doing.

Eileen with Father Daniel on their trip to Mir in 1992

|

Tzila's old house at 52 Zavalna Street in Mir |

|

For Eileen the most important part of her mission was that she was able to trace Sonya Yermolovitch. Sonya, who was over 80 by this time, was living with her daughter in a neighbouring village called Saligorska. Unfortunately Eileen was not able to visit her but through an interpreter was able to make contact. She now learnt why Sonya had stopped writing. Sonya had a friend whose husband worked for the KGB and the friend warned her that it was too dangerous to have anything to do with anybody in South Africa. It was in this same conversation that Eileen learnt that Ignat had passed away. She sent Sonya some money on behalf of her mother and from then on her mother once again sent food parcels to Sonya, until Sonya’s death. Tzila was excited to see all the photographs from Mir as well as to get all the messages from the people that she grew up with on Eileen’s return.

|

In 1993 Tzila decided to fulfill a lifelong dream and go and settle in Israel. She went to live in a granny flat next to the house of her daughter Eileen and husband Noggy. Those were to be very happy years as she watched all her Israeli grandchildren grow up and she became a significant member of the Fridman family. Before she left, she left she had the pleasure of attending her grandson Gavin’s Barmitzvah in South Africa.

The deprivation of the war years remained with her all her life. On one occasion she overheard her son-in-law, Noggy, discussing with Eileen that he would make hot chips for dinner. On his return from work that night he arrived home to find Tzila peeling the last of the potatoes for the chips. Both he and the children were very upset as the peels were their favourite part but Tzila couldn’t understand how they could eat potato peels as that is one of the foods she had relied on for her survival.

|

In Israel she renewed her friendship with Kunya Kagan, who lived in Jerusalem. Once a week Eileen, her daughter, took her to visit Kunya. In 1994 Dani, Eileen’s eldest son celebrated his barmitzvah. This was to be first of many bar and bat-mitzvot of Tzila’s grandchildren that she would attend in Israel. During this time she was again interviewed by Scotland Yard for the trial on Semion Serafanowics.

|

Tzila looking at Sonya and Ignat Yemolovitch’s names on the list of Righteous Gentiles recognized on the wall of Yad Vashem |

After Eileen’s visit to Mir in 1992, Tzila decided that she wanted to have Ignat and Sonya declared Righteous Gentiles. In 1994 a Bielorussian Newspaper printed an article that acknowledged the role Sonya Yemolovitch’s played in saving Tzila’s life, written by Hvedar Gurinovitch . In 1995 Tzila submitted a concise statement of her whereabouts during the war to Yad Vashem in order to nominate the Yemolovitches for the title of “Righteous Among the Nations.” Tzila felt that life had come full circle when on the 6th January, 1996 Yad Vashem awarded them the title “Righteous Among The Nations”.

In 1997 Semion Serafanowics was declared unfit to stand trial for war crimes even though the Crown felt that they had enough evidence to charge him.

|

In 1998 Eileen and Noggy Fridman, Ethel Penn and some of Tzila’s nephews and nieces went to Mir. This time they were able to visit Sonya at her daughter Tonya’’s home. For all of them it was a very emotional meeting. Eileen and Noggy’s children were able to see for themselves all the places that their grandmother had described. It was the first time her grandchildren were able to close the circle of their grandmother’s life.

|

Eileen Fridman with Sonya Yemolovitch in 1998 |

Fridman family - Myer, children- Dani, Yael, Michal and Chaim

together with Sonya, her daughter Tonya,

grandchild and great-grandchildren. 1998 |

Tzila continued to live in Efrat, helping around the house and babysitting her grandchildren where necessary. In November 2001 Tzila had a stroke and from that time her health deteriorated and she was no longer able to care for herself. A carer, Rowena, was employed to look after her on a full time basis as she did not want to move to an aged care facility. In July 2002 her health deteriorated further and after spending time in hospital Tzila was moved to the Tomer Home for Aged Care in Jerusalem as it was no longer possible to care for her adequately at home. She spent one weekend at her flat for her grandson Chaim’s Barmitzvah in October 2002. She was able to be at all the festivities and on the Friday night at dinner she sang songs with everyone at the table. She passed away peacefully on the 3rd February 2003 corresponding to Rosh Chodesh Adar.

She is survived by her children Chonie and Anne Zakheim who live in Israel and their children Devorah, Chava, Chaim, Moshe and Shabtai and their spouses and grandchildren. Her daughter Ethel and Ronnie Penn and their three sons Marc, Gavin and Jonathan, spouse and grandchild, who all live in South Africa, and Eileen and Noggy Fridman and their children Dan, Yael, Michal and Chaim and their spouses and grandchildren who live in Israel.

At the unveiling of Tzila’s tombstone in March of 2003 Eileen spoke about her mother with great love and admiration, “You were such a fighter. Every time before surgery, which was often, you would say to the doctor “Doctor, I survived Hitler, will I survive this?” and you always did because you were a fighter and a survivor.” She spoke of her childhood, “You were always a wonderful mother to the 3 of us. You loved your children to no end.” and of her mother’s deep love of Israel in spite of all Tzila had gone through, “I remember how on העצמאות יום you would watch the ceremony with the soldiers marching and the Israeli flag and cry and say “Who would have believed we would have our own country when we were lying in the forests.” Eileen said goodbye to her mother, “You were a great lady Mommy. We all love you.”

|

Conclusion

In listening to the tape Tzila made for the Shoa Foundation and from the interviews and research relating to the historical background of Tzila I have gained an astonishing amount of knowledge and discovered stories often untold about the holocaust. I have learnt that there were many, but not enough, Jews who were able to escape, hide and fight back against the Nazi tyranny. I have learnt a lot about the secret underground war waged by the Jews and Gentiles against the Germans. I also came to understand that there were Gentiles who went out of their way to help Jews, those who remained neutral, those who fought the Nazis but also those who fought the Jews and those who collaborated with the Germans and were openly anti-Semitic. I realized that this was an event that not only lived with the survivor for all his or her life but also with the descendants. This was a story of many people and how all their actions intertwined with one another led to Tzila surviving the holocaust and of them all being to be reunited once again.

In writing such an in depth account of Tzila Zakheim’s journey I have learnt that one must take every opportunity afforded one and that one should not be afraid to take risks because doing nothing is often a bigger risk and could be more dangerous. I have also learnt that there are people who will risk their own lives to save someone else’s life.

I would like to thank my Aunt Eileen for supplying me with all the information on Tzila’s life, for spending hours on the computer scanning and sending photos and documents to me from across the world. Thank you, too, for often trying to answer the unanswerable questions. And especially thank you for allowing me to tell your mother’s story, which I know is very close to your heart. To my mother Sharon thank you for helping me compile the vast amount of information that I had into a comprehensive story.

|

Bibliography

Nechama Tec (1993) DEFIANCE The True Story of the Bielski Partisans. Oxford University Press: New York

Ilana Ollich (1994) Interview with Tzila Zakheim [video] Los Angeles: The Shoah Foundation

Miriam Swirnowski-Lieder (2002) the German Occupation and Liquidation of Our Little Town. [Internet]. Washington: Jewish Gen Inc. http://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/mir/mir013.html [27th July 2009]

David Twersky, (1998) The Strange Case of Brother Daniel [Internet] New Jersey: New Jersey News. http://www.jewishworldreview.com/cols/twersky080598.html [5th August 2009]

Ari. L Goldman (1991) A Yeshiva Honors Japanese Protector [Internet] New York: New York Times.: http://www.nytimes.com/1991/04/21/nyregion/a-yeshiva-honors-japanese-protector.html [17th August 2009]

Zvi Reshef (2005) Mir Memorial http://www.uoregon.edu/~rkimble/Mirweb/MemorialSite01.html [22nd August 2009]

Author Unknown (2008) The Bielski Brothers; Jewish Resistance and the “Otriad” [Internet] Israel: H.E.A.R.T. http://www.holocaustresearchproject.org/revolt/bielski.html [20th August 2009]

Eliezer Breslin, (2009), Testimony on the escape from the Mir Ghetto by Eliezer Breslin,[Internet]Washington DC: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10007239 [1st September 2009]

Xavier Piat, (1987) The SS Man Who Was a Jewish Partisan… [Internet] Cape Town: Cape Argus Newspaper. http://www.uoregon.edu/~rkimble/Mirweb/OswaldArticle.html [1st September 2009]

Author Unknown (2009) Resistance Plans and Escape from the Mir Ghetto [Internet] Washington DC: United States Holocuast Memorial Museum. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10007238 [1st September 2009]

Author Unknown (2006) UNESCO SITES: Mir and Nesvizh. Minsk: ”Holiday Travel” Travel Agency. http://www.minsk-travel.com/Minsk_Tours_Mir_and_Nesvizh/tour_map [20th September 2009]

Author Unknown (2009) Map of Mir [Internet] Collins Maps. Available from: http://www.collinsmaps.com/maps/Belarus/Hrodzyenskaya-Voblasts/Karelichy/Mir/P662394.00.aspx

[20th September 2009]

Author Unknown (Year Unknown) The Bielski Brothers [Internet] Novogrudok Stories. http://www.eilatgordinlevitan.com/novogrudok/nov_pages/novo_stories_bielski.html [20th September 2009]

Interviews: Eileen Fridman

Sharon Cohn

Footnotes

(1) The boys were Ephraim Sinder and David Sinder who survived the war and settled in Israel. The others included Laike Monicker, Hinde Monike and her daughter. See Yad Vashem Letters

(2) For details on Oswald Rufeisen and his experiences in Mir, see: Tec, Nechama. In the lion's den: the life of Oswald Rufeisen.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

|

Tzila’s daughter Eileen Fridman was interviewed about her mother in a recent YouTube video “How my mother was saved by Righteous Among the Nations in Mir".

The video is about an hour and a half long, describing life in Mir before the war and during the war, Tzila’s escape and survival, her experiences after the war and the journey to South Africa. In addition, Eileen describes family visits to Mir with some of the survivors, showing photos from Tzila's albums. (February 2021)

|

|

| Yisrael Chanan (ben Binyamin) Kopelowicz (1880 - Aug. 1942) & Chayah Sarah (bat Mordechai) Korelitzki/Korelicki |

| |

Pesheh (abt. 1904 - ) & Leibel Dobrin (to SA; 2 children)

Feigel (1906 - 1985) (to SA 1935)

Maishe/Morris (abt 1908 - ) (to SA abt. 1922-23)

Avraham Feivel/Philip (abt.1910 - ) (to SA abt. 1923-24; to Buenos Aires 1936-1937) 2 children

Michael/Michel (Dec 1911- Mar 1943) & Rachel Feld (?- Mar 1943)

Eliyahu/Alec/Alex (Apr 1913 - 1982) (to SA 1928; 2 children)

|

| Yisrael Chanan (ben Binyamin) Kopelowicz (1880 - Aug. 1942) & Etel Lubetzki (?-1937) (married Mir abt 1919) |

| |

Cyla/Tzila (1922 – 2003) (to SA 1947) & Chaim Zakheim (3 children and 12 grandchildren)

Menachem Mendl (1925-1941) |

|

Created February 2011 / update 2021

|