Although the term "knight" was coined back in ancient times with the "equites" of the Roman Empire, most people think of the medieval period when these armored mercenaries hired out their swords to wealthy nobles. I am still astounded by the variety of armor designs and innovations developed during this period.

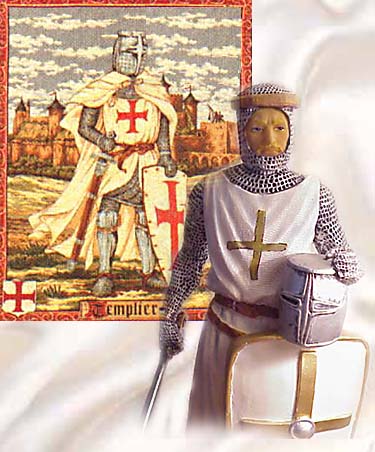

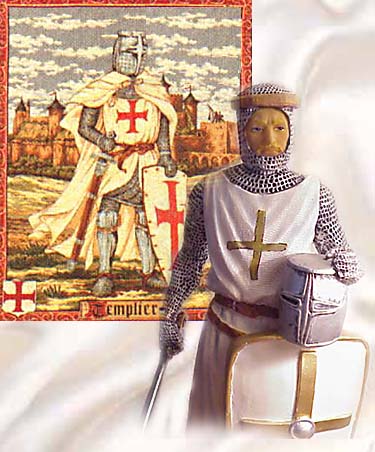

Sideshow Toys offers figures of several knights including Lancelot and the Black Knight but I have not yet acquired them. I did purchase a nice 12 inch resin figure of a Crusader for only $5 at a local flea market. He grips his "Great Helm" in one hand and the Crusader's sword with typical "cruciform" hilt in the other. Historical weapons explains, "Medieval swords appeared in a variety of for ms, but generally had a long, wide, straight, double-edged blade with a simple cross-guard (or "cruciform" hilt). The typical form was a single hand weapon used for hacking, shearing cuts and also for limited thrusting which evolved from the Celtic and Germanic swords of late Antiquity. Over time, the sword became more tapered and rigid, to facilitate thrusting, and began to add a series of protective rings to the hilt, to defend the fingers and hand. This was the birth of the "cut and thrust" or "sidesword."

ms, but generally had a long, wide, straight, double-edged blade with a simple cross-guard (or "cruciform" hilt). The typical form was a single hand weapon used for hacking, shearing cuts and also for limited thrusting which evolved from the Celtic and Germanic swords of late Antiquity. Over time, the sword became more tapered and rigid, to facilitate thrusting, and began to add a series of protective rings to the hilt, to defend the fingers and hand. This was the birth of the "cut and thrust" or "sidesword."

"The now popular misnomer "broadsword" as a term for medieval blades actually originated with Victorian collectors in the early 19th century. The term " broadsword" seems to have originated in the 17th century, referring to a double-edged military sword, with a complex hilt. A medieval sword was simply called a "sword," a "short sword" (in the works of George Silver), or an "arming sword." Further complicating the issue is a "true broadsword," which is actually an 18th century short naval cutlass. The term did not take on the meaning of a wide-bladed medieval sword until the later 19th century. Since then, it has entered popular use by collectors, museum curators, fight directors, and authors.

Ignite plans to release a 12 inch figure of a Crusader from the period of Pope Urban II. Their figure possesses the "Great Helm" but bears the emblem of Richard The Lionhearted on his tunic and wields a battle axe. Ancient Empires explains, "Among the many weapons used for battle during Medieval times, none was more popular and widely used than the Battle Axe, or War Axe. The highly sharpened blades on these formidable weapons could easily pierce armour and shred chain mail worn by opposing knights. The axe was relatively light-weight, allowing it to be an ideal weapon for one-handed battle either on the ground or atop horseback."

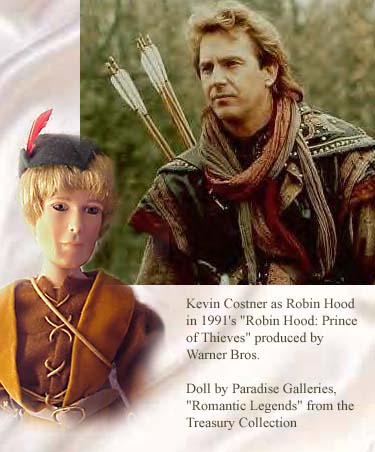

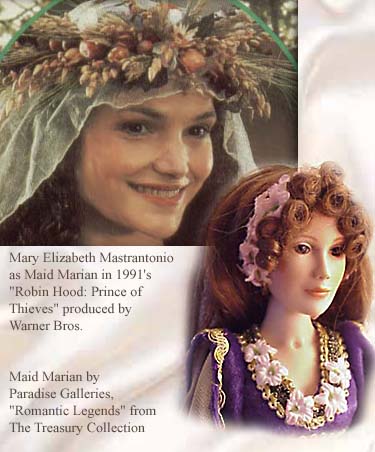

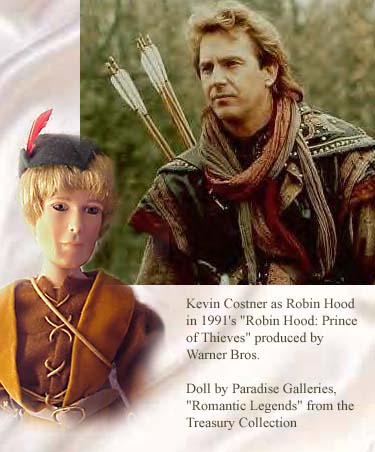

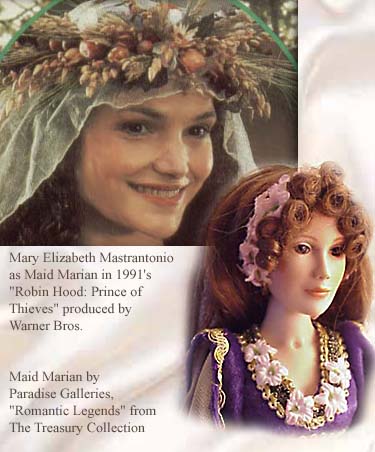

Another popular figure from the Middle Ages is Robin Hood. As a child, I grew up watching Richard Greene as Robin Hood on television. I don't think I ever read Henry Gilbert's novel Robin Hood, reproduced here. Although critics at the time panned Kevin Costner's portrayal in "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves", I enjoyed the film (even if he didn't attempt an English accent!) and particularly enjoyed the music from the work. It provided a particularly majestic background to the entrance of the knights at Medieval Times when I attended a performance there. I like the detailed costumes of Robin and Maid Marian from the Romantic Legends collection of Paradise Dolls but I keep looking for a 12" version of Robin played by Kevin Costner in "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves". The features of the small action figures from this series are realistically portrayed and I was hoping there was a 12" line. I would also very much like a 12" figure of the Moor played by Morgan Freeman and King Richard, portrayed by Sean Connery. Although Sean Connery is always fascinating, I must point out that the real Richard the Lionhearted didn't even speak English.

Another popular figure from the Middle Ages is Robin Hood. As a child, I grew up watching Richard Greene as Robin Hood on television. I don't think I ever read Henry Gilbert's novel Robin Hood, reproduced here. Although critics at the time panned Kevin Costner's portrayal in "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves", I enjoyed the film (even if he didn't attempt an English accent!) and particularly enjoyed the music from the work. It provided a particularly majestic background to the entrance of the knights at Medieval Times when I attended a performance there. I like the detailed costumes of Robin and Maid Marian from the Romantic Legends collection of Paradise Dolls but I keep looking for a 12" version of Robin played by Kevin Costner in "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves". The features of the small action figures from this series are realistically portrayed and I was hoping there was a 12" line. I would also very much like a 12" figure of the Moor played by Morgan Freeman and King Richard, portrayed by Sean Connery. Although Sean Connery is always fascinating, I must point out that the real Richard the Lionhearted didn't even speak English.

I had always assumed Robin Hood was an English legend but I have discovered that scholars have noted a parallel in the exploits of Robin Hood with French outlaw heroes chronicled in "Fouke le Fitz Waryn".

"...the story recounts the Norman settlement, begun by William the Conqueror, on the Welsh border, the feudal rivalries among the Marcher barons, their allies, and the native Welsh rulers, and the complex dynastic relations achieved through marriage and conquest among all these groups. On this historical continuum, which sweeps from the Norman Conquest to the mid-thirteenth century, is superimposed the changing fortunes of one Norman family--the Fitz Waryns," writes Stephen Knight and Thomas Ohlgre n.

n.

"Although there are significant differences between Fouke le Fitz Waryn and the later Robin Hood legend, the works share at least three major episodes, which suggest to us that we are dealing with sources rather than analogues. In Fouke the outlaw's brother, John, confronts a caravan of ten merchants transporting "expensive cloths, furs, spices, and dresses for the personal use of the king and queen of England" (p. 694). Likewise, in the Gest Little John and Much stop the caravan of two monks, fifty-two yeomen, and seven pack-horses transporting the goods of the abbot of St. Mary's Abbey in York. In both works, the two groups are abducted into the forest, where they are questioned about the amount and ownership of their property. The truthfulness of their answers determines whether or not they can keep their goods. Fouke asks, "Are you speaking the truth" (p. 695), while Robin queries, "What is in your cofers? . . . Trewe than tell thou me" (lines 970-71). In both works, the "guests" dine with the outlaws, and, after the meal, they are allowed to leave without their property and money."

"In another pair of episodes, disguise and deception are used to lure the victims into the outlaw's lair. Hiding in the forest of Windsor, Fouke observes that King John is hunting deer (p. 711). Disguising himself as a collier, Fouke greets the king and kneels before him. Upon being asked if he has seen any deer, Fouke, lying, replies that he has seen "One with long horns" and offers to guide the king to it. Going into the thicket, the king is captured by Fouke's men. Fearing that he will be killed, King John begs for mercy, and, after swearing an oath that he will restore Fouke's inheritance and grant him love and peace, he is released unharmed. Returning to the court, the king breaks his oath and plots to capture Fouke. In the parallel episode in the Gest, Little John, disguised as Reynolde Grenlefe, greets the sheriff who is hunting in the forest and "knelyd hym beforne" (line 729). When Little John tells the sheriff that he has just seen "a ryght fayre harte" (line 738) and a herd of deer, he foolishly asks to be taken to the spot where Robin, "the mayster-herte" (line 753), awaits him. After dining with the outlaw band, the sheriff is stripped of his clothing and forced to sleep on the ground. Begging to be released the next morning, he swears an oath that he will not harm Robin or his men in the future. Upon being released, he, humiliated but unharmed, returns to Nottingham where he

John, disguised as Reynolde Grenlefe, greets the sheriff who is hunting in the forest and "knelyd hym beforne" (line 729). When Little John tells the sheriff that he has just seen "a ryght fayre harte" (line 738) and a herd of deer, he foolishly asks to be taken to the spot where Robin, "the mayster-herte" (line 753), awaits him. After dining with the outlaw band, the sheriff is stripped of his clothing and forced to sleep on the ground. Begging to be released the next morning, he swears an oath that he will not harm Robin or his men in the future. Upon being released, he, humiliated but unharmed, returns to Nottingham where he  breaks his oath by plotting to capture Robin at the archery tournament."

breaks his oath by plotting to capture Robin at the archery tournament."

"In the final pair of similar episodes, one of the gang members is wounded in a fight and begs the leader to kill him. Fouke's brother, William, is severely wounded by a Norman soldier and, rather than be captured, he begs Fouke to kill him by cutting off his head. Fouke replies that he would not do this for the world (p. 713). In the Gest (lines 1206 ff.), Little John is wounded in the sheriff's ambush after the archery tournament, and he begs Robin to kill him by cutting off his head. Robin refuses and carries him to safety."

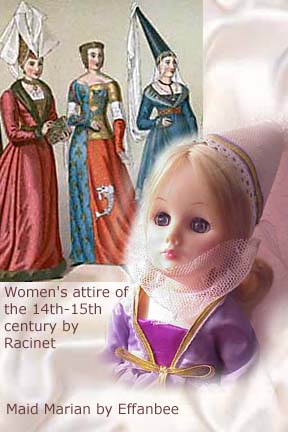

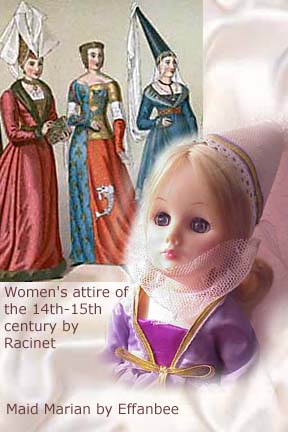

I also acquired Effanbee's version of Robin and Marian. Although Robin's outfit resembles Robin's attire depicted on novel book covers, Marian wears the tall conical headress particularly popular in France from the 14th to 15th centuries. Since the story of Robin Hood is supposed to take place during the reign of Richard the Lionhearted, who ruled from 1189 - 1199, her costume is a little ahead of its time.

Wandering bards and minstrels also made their appearance in the Middle Ages. The first troubador poet was the grandfather of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Poets often recited tales of courtly love where gallant knights fought bravely to impress a lady that was unattainable because she was already married or betrothed.

Wandering bards and minstrels also made their appearance in the Middle Ages. The first troubador poet was the grandfather of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Poets often recited tales of courtly love where gallant knights fought bravely to impress a lady that was unattainable because she was already married or betrothed.

"The "courtly love" relationship is modelled on the feudal relationship between a knight and his liege lord. The knight serves his courtly lady (love service) with the same obedience and loyalty which he owes to his liege lord. She is in complete control of the love relationship, while he owes her obedience and submission (a literary convention that did not correspond to actual practice!) The knight's love for the lady inspires him to do great deeds, in order to be worthy of her love or to win her favor. Thus "courtly love" was originally construed as an ennobling force whether or not it was consummated, and even whether or not the lady knew about the knight's love or loved him in return.

The "courtly love" relationship typically was not between husband and wife, not because the poets and the audience were inherently immoral, but because it was an idealized sort of relationship that could not exist within the context of "real life" medieval marriages. In the middle ages, marriages amongst the nobility were typically based on practical and dynastic concerns rather than on love. The idea that a marriage could be based on love (as in the "Franklin's Tale") was a radical notion. But the audience for romance was perfectly aware that these romances were fictions, not models for actual behavior. The adulterous aspect that bothers many 20th-century readers was somewhat beside the point, which was to explore the potential influence of love on human behavior. - Backgrounds to Romance: "Courtly Love" by Dr. Debora B. Schwartz, English Department, California Polytechnic State University.

At the beginning of the 12th century, male fashion was also used to express sexuality. Almost as a complement to the tall, pointed hats of the ladies, men began to wear shoes with long pointed toes called "pigases".

The origins of these shoes have been, by tradition, placed on the feet of Count Fulk of Anjou, and a need to cover up some sort of foot deformity. This tradition is telling in its Euro-centricity, since we might with more reason speculate that since a continuous tradition of pointy-toed footwear existed in the Near/Middle East since the Sumerians (and remains up to today), perhaps the 12th century Crusaders were influenced by what they found beyond the sea.

The longer shoes were stuffed with moss, hair or wool...bizarre variations of the stuffed pigache toe, such as the "fishtail", "serpent" and "scorpion" shoe, was a fad begun by Robert Cornard in the Court of William Rufus. - Footwear of the Middle Ages, The Costume Gallery.

Some toes were so long they had to be suspended with tethers as depicted by Teresa Thompson on this doll. The London courts apparently thought this was going a bit too far as indicated by a survey published by John Stow in 1598:

"In Distar Lane, on the North side thereof, is the Cordwainers or Shoemaker's Hall, which company were made a brotherhood or fraternity in the 11th of Henry IV. Of these Cordwayners I read, that since the fifth of Richard II. (when he took to wife Anne, daughter to Veselaus, King of Boheme), by her example the English people had used piked shoes, tied to their knees with silken laces, or chains of silver or gilt, wherefore in the fourth of Edward IV. it was ordained and proclaimed, that beaks of shoone and boots, should not pass the length of two inches, upon pain of cursing by the clergy, and by Parliament to pay 20 shillings for every pair. And every cordwainer that shod any man or woman on the Sunday, to pay 30 shillings."

According to History Channel scholars, the length of a man's shoes were meant to represent the size of his male member. If that is the case, this gentleman was obviously very well endowed!

"Eventually, the Church rallied against the extravagance and implied phallic sexuality of the occasionally upturned long stuffed toes, and railed against them as an example of declining morality. Even so, the long toed shoes lasted in the west far longer the second time, only disappearing when, almost overnight, they were replaced by the next shoe fad in the late 1400s - the blunt, wide Kuhmaul, "cow mouth", also known as the "bear paw" shoe." - Footwear of the Middle Ages.

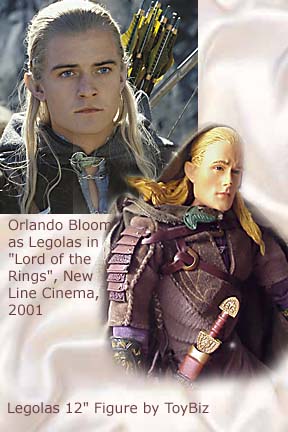

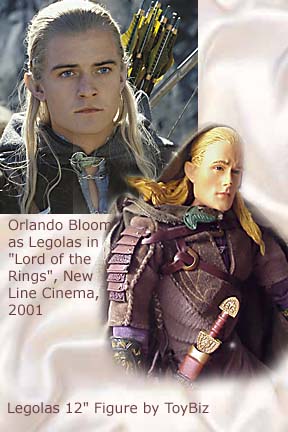

Actually, one of the most realistic costume I have found on a doll -- or uuhumm - "action figure", graces a character from a parallel period, Middle Earth instead of the Middle Ages. The intricately detailed clothing for ToyBiz's 12 inch figure of Legolas from "Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring" is exceptional. In the film, Legolas' archery skills certainly looked like they equalled those of Robin Hood. I do wish the figure would have had rooted hair, however. His long, pale blonde hair was one of his most attractive features. I guess "guys" would have thought it made the piece too much like a doll instead of the more masculine "action figure".

Actually, one of the most realistic costume I have found on a doll -- or uuhumm - "action figure", graces a character from a parallel period, Middle Earth instead of the Middle Ages. The intricately detailed clothing for ToyBiz's 12 inch figure of Legolas from "Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring" is exceptional. In the film, Legolas' archery skills certainly looked like they equalled those of Robin Hood. I do wish the figure would have had rooted hair, however. His long, pale blonde hair was one of his most attractive features. I guess "guys" would have thought it made the piece too much like a doll instead of the more masculine "action figure".

ms, but generally had a long, wide, straight, double-edged blade with a simple cross-guard (or "cruciform" hilt). The typical form was a single hand weapon used for hacking, shearing cuts and also for limited thrusting which evolved from the Celtic and Germanic swords of late Antiquity. Over time, the sword became more tapered and rigid, to facilitate thrusting, and began to add a series of protective rings to the hilt, to defend the fingers and hand. This was the birth of the "cut and thrust" or "sidesword."

ms, but generally had a long, wide, straight, double-edged blade with a simple cross-guard (or "cruciform" hilt). The typical form was a single hand weapon used for hacking, shearing cuts and also for limited thrusting which evolved from the Celtic and Germanic swords of late Antiquity. Over time, the sword became more tapered and rigid, to facilitate thrusting, and began to add a series of protective rings to the hilt, to defend the fingers and hand. This was the birth of the "cut and thrust" or "sidesword." Another popular figure from the Middle Ages is

Another popular figure from the Middle Ages is  n.

n. John, disguised as Reynolde Grenlefe, greets the sheriff who is hunting in the forest and "knelyd hym beforne" (line 729). When Little John tells the sheriff that he has just seen "a ryght fayre harte" (line 738) and a herd of deer, he foolishly asks to be taken to the spot where Robin, "the mayster-herte" (line 753), awaits him. After dining with the outlaw band, the sheriff is stripped of his clothing and forced to sleep on the ground. Begging to be released the next morning, he swears an oath that he will not harm Robin or his men in the future. Upon being released, he, humiliated but unharmed, returns to Nottingham where he

John, disguised as Reynolde Grenlefe, greets the sheriff who is hunting in the forest and "knelyd hym beforne" (line 729). When Little John tells the sheriff that he has just seen "a ryght fayre harte" (line 738) and a herd of deer, he foolishly asks to be taken to the spot where Robin, "the mayster-herte" (line 753), awaits him. After dining with the outlaw band, the sheriff is stripped of his clothing and forced to sleep on the ground. Begging to be released the next morning, he swears an oath that he will not harm Robin or his men in the future. Upon being released, he, humiliated but unharmed, returns to Nottingham where he  breaks his oath by plotting to capture Robin at the archery tournament."

breaks his oath by plotting to capture Robin at the archery tournament." Wandering bards and minstrels also made their appearance in the Middle Ages. The first troubador poet was the grandfather of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Poets often recited tales of courtly love where gallant knights fought bravely to impress a lady that was unattainable because she was already married or betrothed.

Wandering bards and minstrels also made their appearance in the Middle Ages. The first troubador poet was the grandfather of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Poets often recited tales of courtly love where gallant knights fought bravely to impress a lady that was unattainable because she was already married or betrothed.

Actually, one of the most realistic costume I have found on a doll -- or uuhumm - "action figure", graces a character from a parallel period, Middle Earth instead of the Middle Ages. The intricately detailed clothing for ToyBiz's 12 inch figure of Legolas from "Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring" is exceptional. In the film, Legolas' archery skills certainly looked like they equalled those of Robin Hood. I do wish the figure would have had rooted hair, however. His long, pale blonde hair was one of his most attractive features. I guess "guys" would have thought it made the piece too much like a doll instead of the more masculine "action figure".

Actually, one of the most realistic costume I have found on a doll -- or uuhumm - "action figure", graces a character from a parallel period, Middle Earth instead of the Middle Ages. The intricately detailed clothing for ToyBiz's 12 inch figure of Legolas from "Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring" is exceptional. In the film, Legolas' archery skills certainly looked like they equalled those of Robin Hood. I do wish the figure would have had rooted hair, however. His long, pale blonde hair was one of his most attractive features. I guess "guys" would have thought it made the piece too much like a doll instead of the more masculine "action figure".