|

|

|

Introduction

History of Soil as Building Material

Soil is a natural building material in more than one sense. It is used by some animals for their dwellings, and it is likely to be among the very first building materials used by the early humans. Earth buildings are found in near all cultures, and on all habitable continents. Even today, it is estimated that between a third and a half of the human population lives in earthen buildings. Centuries old earthen buildings are still in daily use, even in unlikely locations such as urban Europe. Soil is a natural building material in more than one sense. It is used by some animals for their dwellings, and it is likely to be among the very first building materials used by the early humans. Earth buildings are found in near all cultures, and on all habitable continents. Even today, it is estimated that between a third and a half of the human population lives in earthen buildings. Centuries old earthen buildings are still in daily use, even in unlikely locations such as urban Europe.

There are many obvious advantages to using soil as a building material.

It is cheap and easily available nearly everywhere. It is sculptural

and easily molded. If done right, it is strong and resistant to

weathering. It is easily repairable. It is a friendly material,

allowing everyone to take part in the building process. It also

stores heat well.

There are also some disadvantages to earthen buildings. Hardened

soil conducts heat and is a relatively poor insulator (think of

a ceramic tea cup). It does weather with time, and require regular

maintenance. While the material is cheap, the earthen building techniques

are typically labor intensive.

There is a variety of approaches to using soil as a building material.

Usually, a combination of sand, clay and fiber is used. The sand

serves as an aggregate, the clay as a binder, and the fiber adds

tensile strength, much as in modern day reinforced concrete. Organic

matter, silt, and rounded sand is avoided as these tend to weaken

the hardened mix. The strongest combination will depend on the local

materials available, and is often found through a series of tests.

With all earthen buildings, it is important to give them a good

"hat" and a good set of "boots". The roof must

have wide overhangs to protect the wall from moisture, and the building

needs a solid and tall foundation (typically rock) to keep moisture

from the ground from wicking up into the walls. If these precautions

are taken, the building can last for centuries.

Many traditional approaches to earthen buildings are familiar to

us, while some may be more obscure. Adobe refers to mud bricks. Sod buildings are one exception where organic matter is used. Rammed earth refers to a moist soil mixture stamped into

forms. Straw-clay (or light-clay) is similar to rammed earth,

although the material is straw coated with clay, and it is not structural. Cob is a sculptural technique where the walls are built up

one course at a time using fist-sized lumps (cobs) of moist soil

mixture.

|

Cob - Not Only Corn Cob - Not Only Corn

The word cob is an old English word describing something

that is rounded. We know it from corn cobs, and it is similarly

used to describe the fist-sized lumps of soil used in cob building.

As described above, the cob building technique uses a moist mix

of sand, clay and straw. Walls are built one course or layer at

a time, and lumps of soil mix (cobs) are kneaded into the previous

course, often with the use of a stick. This gives a strong bond

between the courses, and creates a monolithic wall (the top layer

is kept moist between each work period).

Similarly to other earthen building techniques, the exact proportions

of the ingredients will depend on the characteristics of the local

materials, and the strongest mix is found through a series of tests.

Too much clay gives cracks, while an excess of sand makes it crumble.

The final mix should do neither. The proportion of clay in the mix

is typically between 5 and 25 percent.

Cob as a building technique is most known from Great Britain, where

it has been used for centuries.

|

Our Interest

There are many reasons for our interest in cob as a building material,

some of which are described above. The ingredients are cheap and

easily available, it is a sculptural material, and it is an approach

to building accessible to nearly everyone if they have some instruction

and/or guidance.

There are two main ways of using cob in building: Either as the

sole wall material, or in combination with other materials such

as straw bales. The benefit of the first approach is its simplicity,

low cost and thermal mass properties. The benefit of the second

approach is its combination of insulation (straw) and thermal mass

(cob).

We wanted to explore some of the characteristics of cob used as

a sole material for the walls. How does the heat move through cob

walls? How well does cob absorb and retain heat? How slowly is the

heat released back into the building? When is cob as the sole wall

material appropriate, and when it should be combined with an insulating

material?

We chose to do our study at the 120 square feet cob cottage at Maitreya

Ecovillage in Eugene, Oregon. Rob Bolman, natural builder and founder

of the ecovillage, was generous enough to allow us to spend two

weekends there to gather data.

As we had limited time and resources for this particular case study,

we chose to look at one aspect of the thermal characteristics of

cob walls - and use these findings as guidelines for future studies

and preliminary design recommendations.

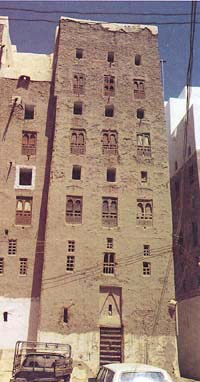

Photos: Devon cob cottage and Yemeni skyscraper

|