Course description

What counts as knowledge in pre-modern societies? What makes knowledge last? What, if anything, differentiates knowledge (scientia in Latin) from wisdom (sapientia)? Stories – narratives -- carry knowledge in its many forms in both pre-modern and modern societies. In his book The Literary Mind (Oxford UP, 1996), Mark Turner suggests that narrative—story--is the foundation of language itself. Yet in the western Renaissance or early modern era, story becomes devalued as "mere story"—so Francis Bacon called it in 1626. Modernity makes history into story's opposite: history gives us fact rather than fiction, story gives us imagination rather than reality. Aren't facts more important than fiction?

Reading pre-modern texts with attention can help us understand the value of narrative and our own positions within a sea of story. We'll use many kinds of tales (a tale is also a "mere story," according to the OED) and their "translations" (meaning "to carry, to transfer") to grapple with representations of self and other, and with the value of imagination and emotion. We'll let the root of education -- educare, to lead forth -- lead us to new sorts of intellectual and emotional understandings as we consider the ways pre-modern cultures produced and saved these tales. We’ll also investigate how and why we’ve gotten our hands on them in 2012 Oregon. Your Clark Honors College literary journey starts, but does not end, here.

Close reading is vital; interpretive muscle grows from it. Written work for the class includes ungraded response papers, two 1500-word formal papers (see paper format instructions above), class presentations, and a comprehensive final examination. Some special events related to the class, such as films or readings, will be arranged during the term.

Your own writing is, of course, both formally and contextually situated. HC 221 H Honors College Literature integrates writing analysis (composition) with the study of literature. Please be advised of two resources: the University Composition Program's resources, and the Teaching and Learning Center in the basement of PLC.

Requirements

- First writing assignment, due Wednesday, September 26. One to two pages, 250 to 500 words. Read the beginning of Gilgamesh. If you were to design walls that bespeak you, what would they show? Of what would they consist? Who would see them? Describe your walls -- the walls that are you -- in the third person and, through the description, provide the reader the walls' -- and your -- meaning. You'll be writing in a long tradition: Mesopotamian students parodied Gilgamesh some 3000 years ago.

- Response papers.You'll write four one- to two-page response papers this term. Check due dates on the schedule below. Response paper are formal in the sense that spelling, grammar, and thinking count; at the same time, these are papers in which to try out ideas, to experiment and challenge yourself intellectually. Here are the steps for writing response papers:

- No fewer than four days before a paper is due, think about something you find intriguing in ourreading, and re-read the text.

- No fewer than three days before the due date, free write, meaning that you make notes, construct an outline, or write a complete draft (this may be handwritten). Use a habitual method, or try a new method you're trying out for the first time. Get something down on paper. Then put away whatever you've written for at least six hours.

- Reread and revise what you've written, again looking at our text for evidence. Have a typed, final copy of your essay complete before noon Wednesday.

- Attach your notes/outline/draft to your finished copy and hand it in.

Do not be surprised if you change your mind utterly while you're writing. Do not be surprised if the last thing you write can better serve as the beginning of the paper. I will read these papers, comment on them, and grade them pass/no pass. Normally, a no-pass paper lacks a thesis and/or contains egregious writing errors. Four passing papers will count as a 4.0, three as a 3.0, two as a 2.0, one as a 1.0. No-pass papers may be re-written, and handed back to me within a week. You may also request that I give any response paper a "grade," meaning the grade it would receive were it a graded assignment: I'll "grade" the paper in order to give you an idea of how grading works on formal papers, but the grade won't "count," per se.

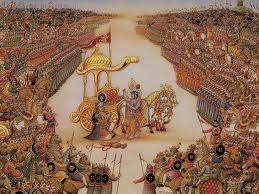

- Graded formal papers. Two five-page (1250 to 1500 words) papers, each of which can use an observation originally explored in a response paper and/or an informal study group. See also tips for topics. Paper 1, due Monday, Oct. 15, will treat Gilgamesh and/or Prometheus Bound. Paper 2, due Wednesday, Nov. 21 , will treat The Book of Job, The Consolation of Philosophy,The Bhagavad-Gita, and/ or Vita Nuova. Comparisons are welcome, but don't lose specificity. Note paper due dates: turn in your papers on the date specified. The first paper may also be rewritten (due one week after returned; include the original paper when submitting the rewrite), with the two grades averaged for the paper's final grade.

- Writing portfolio and reflective essay. During the term, keep all of your work in a folder; at the end of the term, you'll write a reflective essay about your writing, using your portfolio in order to include specific examples of your writing's strengths and weaknesses. Your essay will also treat what you hope to continue to improve in your writing. You'll give me your writing portfolio, with reflective essay, along with your final exam, no later than Monday, December 3, at 5:15 pm. Completing this assignment contributes 10% to your final grade.

- Final exam. Take-home exam, focusing primarily on Hamlet, due no later than Monday, December 3, at 5:15 pm.

Extra credit: Informal study groups.

The learning community of the Honors College affords you an opportunity to test your ideas and grow intellectually in a supportive yet challenging environment. To facilitate conversations about our texts, you can, along with at least one other student, contribute a "discovery" to our Blackboard discussion site before Sunday midnight for each Monday's class. In-person conversations only, please. You're on the honor system for the listing of contributors' names. You may get credit only once for each week, but of course you'll benefit from chatting about many different discoveries. List the discussants' names and include on the Blackboard "discussion site" for that text notes on the conversation, conclusions reached, and at least one question your conversation led to. Again, all this must be posted before midnight on the appropriate Sunday.

If you complete the assignment for each of the eight weeks, you'll receive 3 tenth-points extra-credit on your final grade; for seven, 2; for six, 1; for five, half a tenth.

Grading

The response papers constitute 15% of your grade; the two formal papers, 25% and 30% respectively; the reflective essay 10%; participation, 5%, and the final exam will constitute 15% of your grade. Please note the University's "grade point value" system effective 9/90, as I will be using this system (unless otherwise noted):

|

A+ = 4.3 |

B+ = 3.3 |

C+ = 2.3 |

D+ = 1.3 |

|

A = 4.0 |

B = 3.0 |

C = 2.0 |

D = 1.0 |

|

A- = 3.7 |

B- = 2.7 |

C- = 1.7 |

D- = 0.7 |

Note that a grade of "C" is, according to academic regulations, "satisfactory," while a "B" is "good." That means that a "B" is better than average, better than satisfactory, better than adequate. The average grade, then, is a "C"; a grade of "B" requires effort and accomplishment.