| Home Page Army Picture Page |

Children's

Section |

| The Battle of Cannae |

The Battle of Cannae in the summer of 216 BC is a milestone in Roman

history.

It was Hannibal's finest hour and forced the Romans to learn a

painful lesson.

The Roman legions were perhaps the finest military

units of their day. Their methods of fighting, their training and their

equipment were highly sophisticated and very effective.

But an army on

its own, no matter how devastating, will not win battles. It stands or

falls with its commander. The long line of brilliant Roman military

leaders should largely arise from the lessons learnt against Hannibal.

Having famously crossed the Alps with his elephants, Hannibal descended

into Italy and wrought havoc against the Roman forces.

Major battles

took place at Trebia and at Lake Trasimene, in both of which Hannibal

remained victorious.

A lot is made of the psychological impact his

elephants had on terrified Roman troops.

But by the battle of Cannae

all Hannibal's elephants had died.

Rome put a massive infantry force into the field against him. Force was to be conquered by greater force. Such was the Roman way. The Roman commanders L.Aemilius Paullus and C.Terrentius Varro led a force of 50'000 men or more against Hannibal, who could had 40'000 or less to face them. More so, Hannibal's troops were most likely not of the same quality as Roman legionaries. They were a colourful mix of Gauls, Spaniards, Numidians and Carthaginians.

In theory the Roman sledgehammer should have crushed the Carthaginian menace, but for the way it was to be wielded. Near the town of Cannae next to the River Aufius (Ofanto) the armies met.

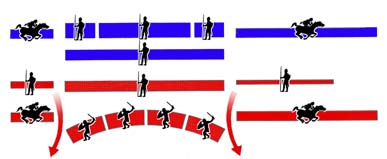

| 1. The Armies meet |  |

| Hannibal first masked his moves as he drew

up his army, by placing his light slingers and spearmen at the

front. Behind them, he positioned his Celtic and Spanish swordsmen in a crescent in the center. On his left wing he stationed his Celtic and Spanish heavy cavalry, on the right he stationed his light Numidian cavalry. Preparing for battle, he now ordered his light troops at the front to fall back and act as reserves. The Romans meanwhile acted as usual. The velites were

positioned at the front to cover their position. Behind them, in the

centre the main body of the legion took its position, with allied

Italian infantry on either side of it. | |

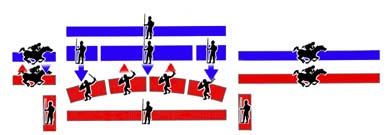

| 2. The Armies engage |  |

| The Romans drove in hard, using their

superior infantry to best advantage. They had their velites

fall back and ploughed into their foe with their heavy

infantry. The cresent of Celtic and Spanish swordsmen buckled and retreated. To the Romans this appeared to be due to their powerful drive into the opponents lines. In fact the troops had been told to retreat. Note: the Carthaginian light troops pulled back at the beginning had by now taken position at the rear of the crescent as well to each side of the crescent. Simultaneously with the advance of their infantry the Roman cavalry on the right wing now engaged the Spanish and Celtic heavy cavalry on the Carthaginian left. | |

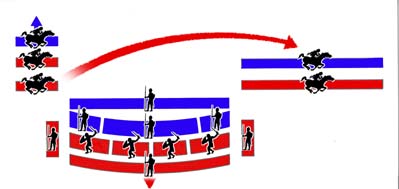

| 3. The Trap |  |

| The Roman infantry kept on driving into the

Carthaginian lines. Forcing them back, they still felt confident

that they were winning. But as they shunted forward and the opponent

withdrew, the light infantry on the Carthaignian side, though itself

staying stationary as it wasn't withdrawing, began to emerge on the

Roman flanks. Worse still, on the wings, Hannibal's Celtic and Spanish heavy cavalry was driving the Roman cavalry back. Combined with the advance of the Roman infantry this meant that there emerged a gaping breach in the Roman line. A large body of cavalry now separated from the Carthaginian left wing and charged across the field of battle to the right wing, where it fell into the rear of the cavalry of the Roman allies. | |

| 4. The Trap closes |  |

| Had the Carthaginian cavalry effectively

defeated the Roman cavalry, the Carthaginian infantry was doing the

same with the Roman legions. The Roman infantry had continued to

drive forward, and had driven itself into an alley formed by the

light Carthaginian infantry stationed at the sides. Shielded by these Carthaginian troops, their comrades who had stayed at the rear could now swing around and come in behind the Roman army. The Roman doomed legions were encircled and beign attacked from all sides. In effect the Roman infantry had been defeated by the opposing infantry, although the returning Carthaginian cavalry helped further accelerate their victory. | |

In effect, the Roman army had defeated itself.

It had solely relied

on the superiority of its legionaries, having lined them up and told them

to advance. No use had been made of the superior numbers, other than to

simply add more ranks onto the back of the advancing columns. As the

Carthaginian units manoeuvered, nothing was done to counter their actions.

One simply did what one had always done - advance.

Such ignorance was

most likely born from the fact that the battles with Hannibal were the

largest contests Rome had ever fought by that time. Despite their earlier

dealings with king Pyrrhus, they most likely had not gathered enough

experience yet in such matters to be able to cope with such huge a

challenge. And the superiority of their legions perhaps made them rely to

heavily on their soldiers alone.

In short, Roman tactics were

non-existent at Cannae. The Roman force acted with brute force, charging

at its dangerously clever opponent like a bull.

Defeat in this battle was a blow from which Rome should be reeling for some time to come. More than ever Rome needed brilliant generals, capable men of intelligence and imagination. Rome needed a Scipio Africanus - and he was soon to emerge to deliver her from the Carthaginian menace.