- Excerpt

from George Underwood's Autobiography - "Life in the Not-So-Fast

Lane"

The years of 1932, 33 and part of 34 must have been the most uncomfortable

years of my life (to date, that is). After the first year at the Chicago

Unit, at least I was

ambulatory, using crutches and ready to face the world again. When I

got home and my

folks saw the problem of getting around and enjoying the outdoors like

all the friends that

I grew up with. The bicycle that I had won was out of the question but

my sister hooked

the wagon to the rear fender with a rope and away we went to the stores,

rides to get me

motivated I guess.

Dad kept busy trying to think of the right gadget to do the job for me.

His first

idea was to convert the old wooden wagon to something like an ‘Irish

Mail’ only with

one lever on the right side and connected to the rear wheel. That worked

OK but the right

arm got tired in a few minutes. Scratch that idea unless you could make

both arms work,

but one had to steer. The next plan was not so simple but for an electrician

it should be

duck soup, right? Read on. He cut a hole in the bottom of the wooden

wagon to hold a 6-

volt automobile storage battery; got a starter motor from the junkyard

and made a pivot

with the old lever. A wooden ‘vee’ belt pulley was mounted

on the side of the rear wheel,

and pulling the lever would tighten the belt at the same time touching

a switch to turn on

the motor. Great so far, so some of the kids gathered to see it go!!

I felt like a test pilot at

the throttle and I was only 8_ years old. Here we go!! I pulled the lever

back and almost

went out the front of the wagon—it was wired in reverse! It was

fixed in a few minutes

and tried again. It went like Hell and had to be tickled to go slow.

It was easy to dump the

thing over when going around a turn too sharp. The brake was another

lever of wood that

rubbed the rear tire. It kept the driver busy making it work but I was

the envy of all my

sudden friends. Deemed, too dangerous, Dad gave up and decided to make

something

that would be more of a machine than these “Rube Goldberg” things.

|

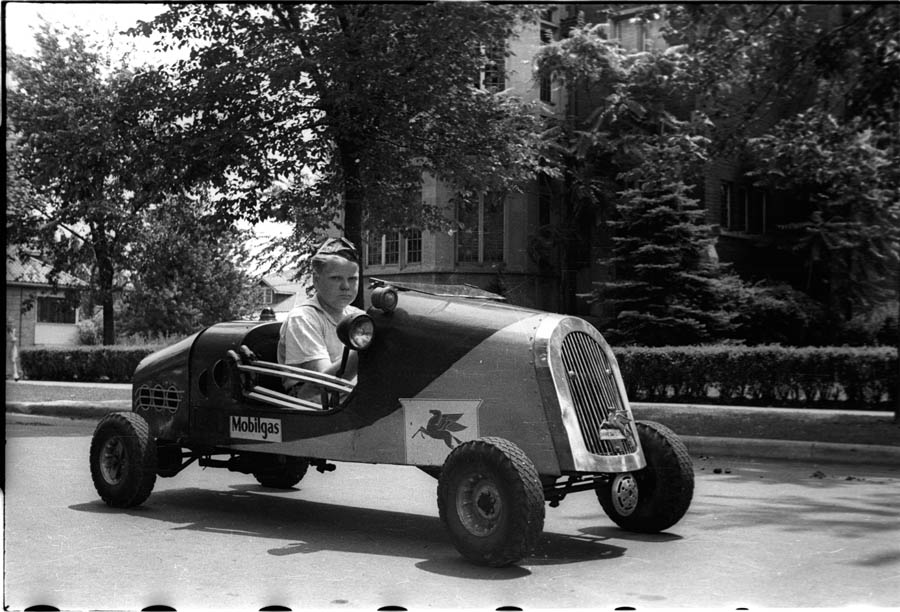

- It was amazing to see what was growing in the basement.

A single-cylinder, one horsepower

gasoline engine built by Maytag Co. for washing-machine power, showed

up

from a friend who had an engine shop and store. The cost was $52.00;

it had valves in the

head with exposed rocker arms and push rods from the camshaft. Instead

of a rope starter,

it had a segment gear on a lever that would engage the cranking ratchet.

Seemed great

but trying to get it to run on the concrete floor to check it out was

almost impossible,

without anchoring it to a frame or bench. Had to wait till later. No

plans were drawn, just

chalk marks on the floor while I watched what was happening and learning

a whole lot

that I used later in my life. He started the frame with a long piece

of 1_" channel; cutting

notches with a hand hacksaw to allow the steel to be bent into a frame

that was about 7 ft

long and about 24 inches wide. The ends were narrower to give a taper

to the front and

rear with straight sides for about 36 inches. When satisfied that this

was the right shape

he wanted he took it to the neighborhood tire shop who had a welder man

that got

interested and did the work after hours for free, I think. All of the

joints were heavy

brazed and looked very professional. The rest of the work was done in

a similar manner

The clutch was a unit from a shop where the machines were driven by overhead

belts and long drive shafting. It was a ‘cone type’ that

had a tapered cone and by moving

the hub sideways a finger would slide up the cone and would turn a bolt

about _turn,

enough to clamp a split hub tight to grab the rotating inner hub. With

a system of a bell

crank and lever the clutch could be operated easily and lasted for the

known life of the

vehicle.

The clutch and brake were on a jackshaft with a large driving pulley

and another

pulley and ‘vee’ belt to a wooden pulley on the rear

axle; only one tire was driven. The

brake was from the junkyard again and was a Plymouth emergency brake.

It was the

easiest thing to connect, just one lever with a thumb ratchet release

on the lever for

parking. The steering wheel was something else. Back to the junkyard,

Dad selected the

steering column from a Ford Model ‘T’. The wheel was

fully 20 inches in diameter, so

we asked our Shriner friend, who also made the wood pulleys, to make

a steering wheel

about 14 inches in diameter—no problem, so a few days later

we had a beautiful

machined wood wheel of laminated pieces. The arms of the Ford wheel were

cut to fit;

now all that was needed was something to use to steer.

|

|

- A set of four balloon-tired airplane tail wheels showed

up that had needle

bearings and an eight-inch rim size, complete with air hose fittings.

Lots of fun rolling

these around the basement and getting in trouble while work was being

done! My sister’s

boyfriend (Anthony Trendler) and later her husband was there even on

date nights to help make some of the

parts. The rear axle was simple because the tire on the left side could

idle while the right

one was anchored to this rotating axle. Needle bearings were used with

inner recession on

the axle. The rear springs were fashioned by another friend of Dad with

a forge shop.

Junk single leaf springs were heated and forged until the bearing shells

were a tight fit.

The front, of course was different. One spring was forged to fit around

the rigid axle, one

side was welded, the other free to turn and not fight the other over

uneven ground. A

Masonic friend owned Pokorney Machine Co., who volunteered to make the

steering

knuckle system. Great work was done to connect to the Ford reach rod

and cross rod with

a cantilever axle to fit the wheel needle bearings. Worked OK for many

years with no

trouble. Well here we were with a frame and drive system, but no body!!

No problem,

with some wood pieces the steering columns was supported and I was told

to try to drive

the thing in the spring after my ninth birthday!! It worked great! The

few old photos show

this time of my life. If you think the electric wagon was exciting to

my friends, you

should have seen the group of bicycles that followed and the riders begging

for a ride on

the car frame!

At this time in the Depression little cars that had the Barney Oldfield

look were

popular but to buy one would be around $300. Too much for my folks. Tony

Trendler,

my sister’s boyfriend worked in his father’s sheet metal

fabricating company shop. To

him sheet metal work was ‘no problem’. He made a stainless

steel false grill frame with

rods to make up the ornamental front. The other cars mentioned above

were tiny

and kids got in with the aid of a shoehorn they were so tight. With me,

and legs that

didn’t bend, it required something different, so the left side

of the front hood was built

with a piano hinge door to allow easy entry. Tony fashioned its feature

along with a

removable bonnet over the engine and jackshaft that made it look like

a real vehicle. The

car needed a windshield, for a possible rainstorm; so back to the junkyard

and the wing

type window from a touring car was cut to be symmetrical and mounted

on the hood.

Looked and worked nice. What to do in case it got dark? The battery from

the electric

wagon was mounted inside the hood behind the grill. Two small running

lights were from

some kind of car and a small red light was put on the rear. A horn was

also mounted

behind the grill and sounded official when needed. The only damage done

to the car was

caused by me when following a group of ponies in the alley that gave

children rides for a

few nickels. A pony didn’t like when I honked the horn so it kicked

and bent several of

the rods in the grill. Never did that again.

My dad’s goal was to get me mobile—well I sure was. The car

was used only in

the summer time and spring and fall when weather was nice, and after

school if time

allowed. I drove the car on the streets as well as sidewalks when necessary.

Looking back

on this would scare me if my kid were riding in traffic with this little

midget racerlooking

car; but I made it until I moved up to a 1941 Oldsmobile Hydra-matic!!

The car

was kind of short on power to go up hills; a running start was required

to make the hill at

Ridge Boulevard in Rogers Park. On level ground it could make 27 mph.

That seemed

fast sitting below the height of the wheels on the cars in the next lane.

It had enough

power to pull two wagons on level pavement. I enjoyed doing this because

the wheels on

the car would straddle the manhole covers but wagons wouldn’t.

A good friend who lived

on the next block on Coyle Avenue (also handicapped and could not walk

because of

Muscular Dystrophy), used a wagon all the time. He got irate when I pulled

him over a

cover once in a while. Still, we were friends all through college and

work years. More

about that in another chapter.

Remember the description of the rocker arms? Well if they overheated

they’d

freeze, the rods would buckle, and you’d be ‘out of business’.

I learned how to fix them

by replacing with ones in the little toolbox with small wrenches and

feeler gauges. I

usually carried a length of clothesline so if really stuck, a nice person

like an insurance

salesman would tow me home! Looking back on this, I sometimes wonder

if I was crazy

to trust the car by getting so far away from home, but I guess I had

faith or guts (or both).

On long trips, I would be accompanied by my sister and Tony or some one

else, riding

their bikes. The farthest that I can remember was to Glenview Naval air

Station in

Glenview, my sister was worn out but I remember having fun. The car had

to be

lengthened by about 6 inches when I was about 13 to be able to fit in

it.

One great event I can’t forget was riding around the neighborhood

and stopping in

the alley every so often to see if my sister had her first baby. “Is

it here yet?” I’d ask.

Finally I heard, “Yes, it is a boy!”—my nephew, Carl

A. Trendler. The arrivals of the

others in he family; Bob, Loretta, and Gary Trendler were not as spectacular

as Carl’s

and for not mentioning theirs, I apologize. The car was stored under

the back porch in the

winter and it was hard on the paint job. It had to be repainted by hand

several times,

usually with a different paint or color scheme to make it more ‘jazzy’.

Fuel was not much of a problem. The tank held less than a gallon and

would last

almost a week unless I used it on longer rides. Going to the gas station

was something

else; the nozzle on the hose was too large for the tank so a funnel was

usually in the car.

The most popular station that was convenient was the ‘Socony-Vacuum’,

now Mobil

Corp. For one dollar, you could get 12 gallons plus a dish or two. This

was not high

finances, but the guys at the station offered free gas if they could

put the decal of the

Flying Red Horse on each side of the hood—why not? They were flying

until the car was

sold years later.

|

|

- Like mentioned above, it was fun to ride on the sidewalks,

but little kids were

always getting in the way and so, not to hurt them I drove in the streets.

You might recall

that these streets were not too wide and today most of them are ‘one

way’. Most of the

times I drove around the neighborhood, a trip through Rogers Park was

included. It had

nice things like a lagoon with ducks and swans, and a small zoo for tots

to get excited

about and enjoy. I know because my own children liked to go there too!

When on the

pavement in the park, I had to watch kids and adults coming around the

next turn. The

park was policed by the Park District Police of Chicago and the name

of the regular

officer in the park was Pat. He would stop me often by raising his hand

and asking,

“Where is your License Plate?” or, “Where is your vehicle

license?”, to which I

answered, “I don’t have one.” I don’t know if

this satisfied him or if he just liked to look

at the car.

|