Qing1

From Ming to Qing

Since 1589 the Jurchen had been allies of the

Chinese in their war against the Japanese invaders of Korea (1592-1598). Their leader, Nurhaci, unified the peoples of eastern Manchuria (Liaoning province) who were trading with pearls, fur,

ginseng, and mining products.

In 1601 Nurhaci created a military administration

which was headed by aristocrats from the clans of the alliance. These military

units were modeled after Chinese border garrisons that had been established

during the Ming. They were called Inner and Outer Banners, the Inner Banners

consisted predominantly of Manchus, while the Outer

Banners were kept for auxiliary troops made up from Han Chinese, Mongols etc.

In 1609 the Manchus formed an alliance with

the Eastern Mongols against their Western relatives. This alliance with the

Eastern Mongols, the enemies of China, made the Manchus

to enemies of the Chinese as well.

In 1616 Nurhaci, who was the leader respected

by both Manchus and Mongols now, proclaimed himself

Khan and founded the Later Jin dynasty. The name was chosen in commemoration

of the first Jurchen dynasty with the name 'Jin

dynasty' that had ruled in the northern territories of what had become the living space of the Manchus

in the meantime and had conquered the northern territory of the Song in 1126.

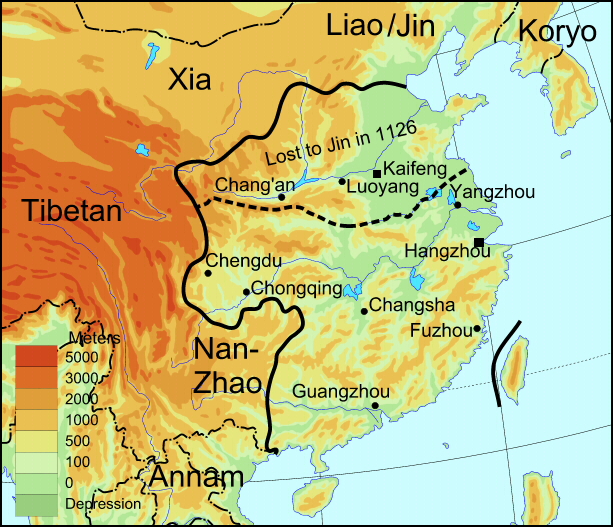

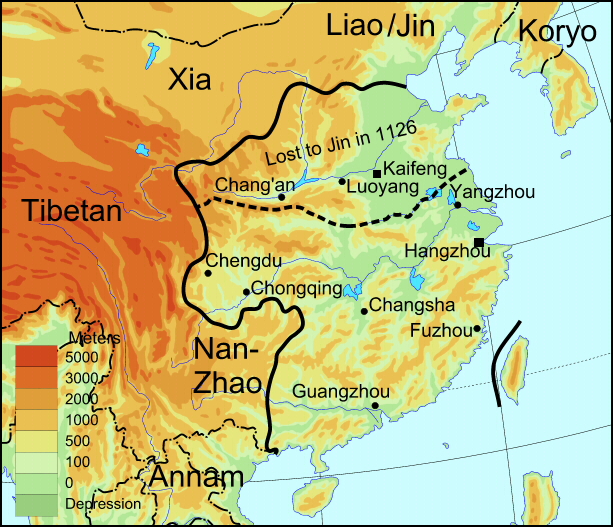

Map of Jin territory ('first Jin') conquered

from the Song in 1126.

A few years after the proclamation of the Later Jin the Manchus began attacking the northern territory of China and finally established a capital in Shenyang, called Mukden. Nurhaci died soon

after the founding of the capital and was succeeded by Abahai

(1627-1643). In order to create a functioning state, Abahai

imitated Chinese institutions with the assistance of Chinese civil and military

advisors.

In 1635 Abahai proclaimed the name 'Manchu' to be used for his people

(instead of Jurchen) and the dynastic name Later

Jin was changed to Great Qing [=Clear, Clarity].

With the military and strategic strength that the Manchu had gained and with

their political unity and administrative organization all prerequisites for

a stabile rule had been established.

When the conquest of China began the Manchus

were assisted by a group of Chinese generals, most of whom

hailed from former border garrisons in Liaoning province. Fan Wencheng

(1597-1666) and Wu Sangui (1612-1678) were the most

important among them. These generals knew Chinese and Manchu and had been

accepted into the Inner Banners. They gained a position that was similar to

the status of the eunuchs in the Ming though they did not gain excessive power:

They were entrusted with the internal administration of the palace and

with the control of the imperial workshops.

The conquest caused resistance which was quelled with strict laws:

In 1645, when Abahai established the capital

of the Great Qing in Beijing, all Chinese inhabitants

of the northern part of the city were expelled and had to settle in the southern

part, reserved for the non-Manchu population. All Chinese inhabitants of Beijing who were suspected to have smallpox were

to be expelled from the capital. Under the pretext of keeping the epidemy

under control the Manchu administration simply banned all Chinese persons

with skin diseases from the capital.

Chinese men were ordered to wear Manchu hairstyle: The forehead had to

be shaved, the remaining hair was braded in a pigtail

which was wound around the head. The same hairstyle, which was popular among

peoples in the steppe, had been enforced on Chinese men by the Jurchen during the Jin dynasty in the 12th century.

In the same year - 1645- enclaves for exclusively Manchu inhabitants were

founded in the northern provinces of China. The Manchus

enslaved prisoners of war and landless peasants who had to till the land for

them. This harsh rule over the Chinese population was eventually given up

because the Manchu realized that lean taxation and a better rule would guarantee

the cooperation of the non-Manchu majority of the population much easier than

brutal force. Nevertheless, they still tried to enforce laws of segregation

and in 1668 all Han Chinese were banned from settling in Manchuria. This ethnic segregation had cultural and

economic reasons: intermarriage was forbidden to keep up Manchurian heritage

and minimize sinicization and at the same time the

exploitation of the ginseng production, a great source of income, remained

in Manchu hands.

The conquest of the southern parts of China was more challenging than establishing a

new rule in the north. Comparable to developments in the Southern Song, the

remnants of the Ming court had fled south and had proclaimed a new emperor

in Nanjing who headed the Southern Ming dynasty. But

resistance was broken by force. Yangzhou, which had been defended with an iron hand

by the Ming-loyalist Shi Kefa

was taken by the Qing and the emperor had been handed

over to the Qing when Nanjing fell a few days after Yangzhou.

The rest of the imperial family and the court fled to Yunnan province in southwestern China and again

a new emperor was proclaimed. He and his entourage could not withstand the

perpetual attacks by general Wu Sangui, who fought for

the Qing. The emperor took refuge in Burma, was captured in 1661, brought back to China,

and strangled in Kunming.

The resistance in the south lasted some 50 years and was assisted by figures

like Zheng Chenggong (1624-1662),

a Ming loyalist who survived by successfully

combining piracy and trade. He was closely associated with the Southern Ming

court and even allowed to use the Imperial family name, Zhu. This privilege

brought him the nickname 'Guoxingye', ‘Excellency

with the royal family’s name’ which was transliterated by the Dutch and others

Westerners as ‘Coxinga’. In order to subdue him

and his fellow pirate-loyalists, the Qing government

in 1662 evacuated the entire coastal regions from Shandong to Guangdong. All coastal villages and cities were destroyed,

the inhabitants had to move to the hinterland. The

resulting destruction of Chinese trade relations facilitated the intrusion

of Western merchants from Portugal, Spain, and Holland in East Asia.

A stern Ming loyalist, Zheng Chenggong expelled the Dutch from Taiwan and rebelled against the Qing.

Shrine for the

national hero, Zheng Chenggong in Taiwan

Shrine for the

national hero, Zheng Chenggong in Taiwan

As mentioned before, the initial rule of the

Qing had been facilitated by the service of Chinese officials

who had served under the Ming as well. Some of them became military governors

under the Qing and obtained a rank similar to imperial

princes. They were entrusted with the administration of large parts of southern

China, areas that eventually became rather autonomous and finally sought independence

from the central administration in Beijing.

Three of these governors became increasingly powerful:

Wu Sangui who had

destroyed the army of the rebel Li Zicheng and then

had chased the Ming loyalists to Yunnan. He had kept his troops under arms and while

financially supported by the Qing government, finally

controlled the south-western provinces of Yunnan, Guizhou, Hunan, Shanxi, and Gansu.

When the governor of Canton,

Shang Kexi (1604?-1676)

tried to obtain autonomy from the Qing, the freedom

of the ‘prince-like’ military governors was curtailed. Wu Sangui

and the military governor of Fujian, Geng Jingzhong (?-1682) rebelled

openly and won over several other governors, including the son of Shang Kexi named Shang Zhixin, for their cause. But

eventually they had to show their submission to the Qing.

After Wu Sangui had died in 1676 the Qing army successfully recaptured the southern and southwestern

provinces. As soon as this military challenge was ended in 1681 with the conquest

of Taiwan, the Qing dynasty was in command of the entire

territory of China.

Territory of the Qing Dynasty

Shrine for the

national hero, Zheng Chenggong in Taiwan

Shrine for the

national hero, Zheng Chenggong in Taiwan