Hist 387_7

The end of the Qin

and the beginning of the Han dynasty

Due to the Legalist Shang

Yang’s reforms the population of Qin was divided

into groups of five and ten households, breaking up extended family clans

and enhancing state control over the populace.

Population registers were created – the first attempt

by the state to plan and control state revenues and army recruitments by conducting

a systematic census.

This strict supervision of the population had a psychological

effect which influenced the development of religious belief systems: the bureaucracy

dominating the people through census and law in life was projected into the

neitherworld. The administration of the supernatural

realm was thought to bestow a certain life-span for everybody and recorded

one’s behavior in life for which one was to face a neitherworld

jurisdiction after death. Communication with the spirits of the other world

worked through prayer and offerings of incense and money

that was burned.

The death of the first emperor caused multiple problems

regarding the succession to the throne. Zhao Gao (?-207 BCE) placed the second son of the emperor

on the throne, thus ignoring the emperor’s wish to have his first son succeed

him. Worse even, through an intrigue he ordered the first son to commit suicide,

had chancellor Li Si excecuted,

took over his position and finally had the second son of Qin

Shihuangdi killed as well. Yet Zhao enjoyed his

strong position without opponents only for a few months: The last Qin

emperor, still a young boy, ordered Zhao to be removed and then surrendered

to the rebels who attempted to overthrow the Qin.

The burning of books in 213 BCE and the

murdering of the scholars in 214 BCE

The aversion against Confucian values

and their emphasis on the necessity to link one’s rule to the sage kings of

antiquity is said to have inspired the first emperor to conduct a burning

of books (= all Confucian Classics and historical records reporting of the

rules of the sage kings; only books on agriculture, law, divination, and medicine

were exempted), and the cruel execution of 460 Confucian scholars who opposed

him.

This report needs to be read with care for several

reasons. First, book production consisted of preparing bamboo slips, attaching

them to another and inscribing them, a process which limits the amount of

copies produced of books in the first place.

And though punishments like beating or fining were common practice

for instance towards officials who had failed to keep the laborers assigned

to them under control it remains questionable whether the murder of the scholars

actually took place or is an exaggeration on the side of historiographers

in order to denounce Qin cruelty. They may have

used this description for the justification of the overthrow of Qin

by the Han, very much like the Zhou legitimized their conquest of the Shang: the evils of Qin made a the

overthrow and a transfer of the Mandate of Heaven in evitable.

The burning of books and the torture of Confucian scholars

Archaeology helps to put Han historiography

in perspective: the tomb at Shuihudi of a Qin official named Xi (d. 217 BCE) included 1.155 documents

written on bamboo slips. They included texts on divination and law. The law

texts speak a different language than what is purported as ‘lawless cruelty’

by Han historiography. Though Qin punishments were

harsh (forced labor, amputation, cutting off the nose, tattooing, marking

the face etc.) there was a systematized law code for an array of different

crimes which seems to have been followed with some care.

The founding of the Han

Map of the Han Dynasty

After a dramatic victory over his contender,

the noble Xiang Yu of

Portraits of Liu Bang / Han Gaozu

One of the first measures in office

was that Liu Bang created a new nobility, a class

that the Qin had eliminated not without reason. Of common origin himself

he instantly enfeoffed his brothers and sons as

kings and 150 of his followers as marquis’: the re-establishment of a feudal

system. One third of the Han territory including the capital remained under

his control, the rest was ruled by his relatives.

The Han government

- central

administration:

emperor

tax collectors army supervisor government officials

- local administration:

tax collectors,

population registration, justice, maintaining infrastructure, recommendation

of candidates for office

Foreign affairs

The northern neighbors became and remained

an oppressive force. Throughout history it should turn out to be easier to

‘buy peace’ from the Xiongnu and Xianbei

by establishing friendly ties through sending gifts such as textiles, wine,

and princesses than fighting back their endless attacks.

When Gaozu died in 195 BCE,

his wife Empress Lü, took over as a regent for their 15 year old son. His ‘reign’

lasted only eight years. After his death his mother continued to reign for

two other infant emperors who died after suspiciously short lifespans. When Empress Lü finally

died herself in 180 BCE, the imperial Liu clan tried to get rid of as many

Lü relatives that had come to high ranking positions

as possible.

A stately tomb in the Han

Excavation in progress

Reconstruction of Lady Dai's coffin

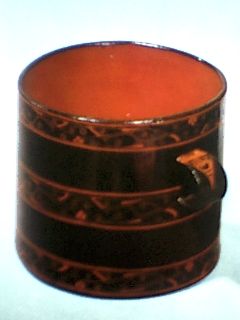

Lady Dai’s tomb at Mawangdui

- perfectly preserved corpse (1,54 m tall;

34,3 kg)

- inventory of funerary objects written on bamboo

- grave goods: 154 lacquer

vessels; 51 ceramics; 48 bamboo suitcases with clothing and household goods

- 40 baskets filled with 300 replicas of gold pieces;

100,000 bronze coins

- food: rice, wheat, barley,

millet, soybeans, red lentils

- recipes for – vegetable

stew with meat

beef & rice stew

dog meat & celery stew

deer stew

fish stew

bamboo stew

seasonings: salt sugar, honey, soy sauce, salted beans

Lady

Dai

Lady

Dai

Lacquer cups and fodd containers

Dark and red gown

Gloves

and wooden figurines (servants)

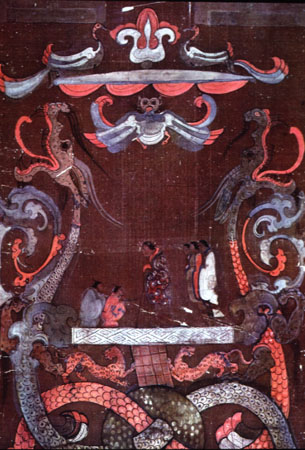

The burial banner of Lady Dai

Burial

banner

Burial

banner

Top section:

- realm of the immortals,

entrance guarded by gods of destiny, keeping record of lifespan

- moon with toad and

rabbit

- sun with (three-legged)

raven

- Queen Mother of the West/: reigns the realm of

the immortals in the

Middle section:

- Lady Dai’s body soul in her tomb; feast with

ritual vessels, offerings (chopstocks placed upright

in the bowl)

Lower section:

- shrouded body: death

The library of Lady Dai’s and King Li Cang’s son, a military official (d. 168 BCE)

- Book of Changes (Yijing)

-

Book of the

Way and Virtue (Daodejing)

-

Intrigues of the Warring States

-

Texts on law, fortune telling, sexual techniques;

three maps

The reign of Han Wudi

(r.140-87 BCE)

After Empress Lü

died in 180 BCE two emperors had come to the throne and ruled partly under

the supervision of regents; during this period the power was taken out of

the hands of the relatives of Empress Lü and the

number of feudal kingdoms was considerably reduced.

Han Wudi was to become a

powerful ruler who reigned for 50 years. He came to the throne aged 15 and

ruled for the first nine years under the supervision of regents. When they

died, he remained the sole

authority until his own death in 87 BCE. He relied on advisors

though, the most influential of whom was the philosopher Dong Zhongshu (175?-105? BCE). His ideal

of ruling saw the position of the emperor as a servant to his state. The Confucian

vision of a benevolent rulership and mutual responsibility

of ruler and subjects formed the basis of his philosophy of statecraft.

Dong saw the larger pattern in which every human including

the ruler was integrated, as dominated by the complementary forces of yin

and yang and the alternating dominant phases of the five elements: wood, fire,

earth, metal, and water.

In order to disseminate Confucian learning, Han Wudi set up an academy for scholars who became experts of

the Five Confucian Classics which they taught to selected students, a group

that then provided the candidates of which the emperor selected new officials.

Han Wudi chose most of his officials from low-ranking

families, securing their boundless loyalty founded on gratitude.

Expansionist politics

The emperor consolidated power by reducing

the feudal kingdoms and pacifying border regions in the West (

Sima decided to

live with the shame but fulfilled the promise he

had given his father on the deathbed: He completed the historical records

his father had begun. The amazing intellectual accomplishment remained the

model for all dynastic annals.

Expansion of the Han Empire - Expansion of the Xiongnu heartland

After Han Wudi’s death a

period of changing child emperors dominated by changing regents determined Han

politics.

Economic problems

Revenues never quite matched expenses

during Han Wudi’s rule. Therefore monopolies for salt and iron were set

up, later extended to copper, bronze, and alcohol. While lucrative for the

state, the monopolies were severely criticized by Confucian scholars as burdens

on the people recruited to work for them and pay for the products. In addition the scholars warned the officials

not to engage in trade, especially disgraceful was

in their considerations the trade with the neighboring ‘barbarian’ and aggressive

Xiongnu. The officials believed that trade was bound to corrupt

the officials. Yet trade had already become an integrated part of society

and propelled social mobility. Merchants had to put up not only with the fact

that their profession was despised, but also because they paid 100% more taxes

than artisans for property and transport vehicles such as carts and boats.

(e.g. for a property worth 4,000 coins merchants

paid 240 coins, artisans 120). Land could be traded and as time went by large

estate owners were landlords who either had been enfeoffed

with land or had increased their property by buying continuously. As true

lords of the communities landowners tried to evade taxes wherever possible.

Therefore the government tried to limit landownership, a measure that was

only effective during the short period of the rule of former chancellor and

formidable diplomat Wang Mang and his New (Xin)Dynasty

(9-23 CE).

Wang Mang Interregnum

Wang Mang

intended to create the ideal society of the Zhou as portrayed by Confucius.

He started to limit the possession of land and abolished slavery. A politically

well versed strategist and diplomat he linked his ideals to the past as captured

in the Rites of Zhou. He

abolished the trade of slaves (serfs) and the trade of land. Instead he installed

a system of land distribution. His measures were reversed though when the

Changes of the Yellow River throughout Chinese history; currently the stream

flows into the sea south of the city of Tianjin and north of the Shandong

peninsula

The flooding left many people without land or income. Under

the leadership of religiously inspired 'saviours', one of them a woman called

Mother Lü, uprisings contributed to the political destabilization. Leaders

of the Han imperial Liu-clan formed an alliance with the 'Red Eyebrows', an

enormously strong army that grew out of an uprising led by Mother Lü,

in order to defeat Wang Mang. [They painted their eyebrows red in order to

be able to distinguish between friend and enemy in war.] Wang Mang's dynasty

ended with his death and the Liu's founded the Later Han Dynasty (25 C.E.),

but now they were in the position to be threatened by the 'Red Eyebrows' themselves,

who wanted to have their own state. It took two more years until they defeated

the 'Red Eyebrows' completely. They could accomplish this only with massive

support by wealthy landholders who had their own private armies.

The devastation caused by the flooding was one more reason for the migration

wave to the south. The threats by the neighboring Xiongnu was the other force

that made thousands of families, aristocratic or poor, leave their land and

homes and try to find a new home somewhere in the south, where soon a new

culture composed of local traditions and influences brought along by the immigrants

flourished.

The capital was moved to

His daughter Ban Zhao (ca. 45-120 CE) wrote

the most famous book on the education of girls, titled ’Lessons for Women’

[or "Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies"];

she had been married at the age of 14 and later, after her husband had died

and her children were coming of age, served as tutor and advisor to empress

Deng.

The 'Admonitions for Women' which she wrote when she was 54, is an

important source of information on women's life as well as the ideals and

standards set for them in their education, which required that women should

be able to read and write since educated [elite] women were considered 'capital'

for the family in marriage negotiations; in addition: virtue and physical

perfection (report of Maid Wu on the future Empress Liang Nüying, d.

159) were requirements added to the concept of an ideal woman which consisted

of folowing the four demands of:

1. womanly

virtue: chastity and loyalty

2. womanly speech: no chatting

3. womanly bearing: high standard of personal hygiene and hygiene in household

organization

4. womanly work: weaving, sewing, food preparation

The low status of women is also symbolized in a rite performed three days

after birth. According to Ban Zhao the following acts are performed:

1. the baby girl is laid below the bed to indicate her low status within the

family

2. she is given a potshed as a toy symbolizing the hard work she has to be

committed to throughout life

3. three days after birth she is presented to the ancestors to introduce her

as a new future servant to the ancestors

The period of three days between birth and the introduction of the new family

member to the ancestors was often the time in which female infanticide occurred

if the woman/family was not capable of raising a(nother) daughter.

Ban Biao's son, Ban Gu

(32-92 CE) excelled in the composing of rhapsodies and continued to write

the ‘History of the Former Han’, begun by his father. The work was completed

by Ban Zhao after Ban Gu’s death.

Idealized image of Ban Zhao writing calligraphy