The Zhou: Western Zhou (1044-771 BCE) and Eastern Zhou (770-221 BCE) [divided into Spring- and Autum Period (722 - 481 BCE) and Warring States Period (475/481-221 BCE)]

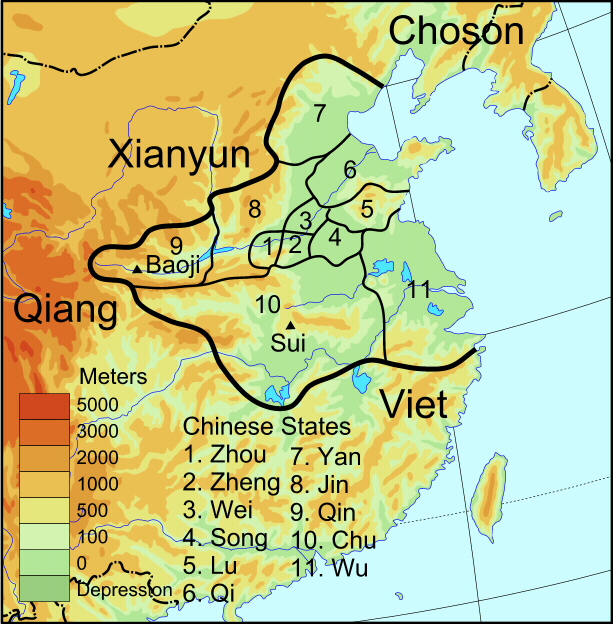

Map of Zhou Dynasty territory

Among the non-Shang mentioned in the oracle bones are the Qiang (who were found as sacrificed prisoners-of-war in Shang tombs) and the Zhou, who came to be the successors of the Shang.

The concept of the Mandate of Heaven

The Zhou dynasty (1045-256 BCE) did not only leave written

sources in the form of bronze inscriptions but was also described in written

sources, among them the classical texts of the Book of Songs (Shijing)

and the Book of Changes (Yijing).

Sima Qian reports about the concept of the 'Mandate of Heaven'

as its first use was described in the fifth part of the Classic Book of

Documents, the Book of Zhou (Zhou shu in the Shujing).

They Zhou used this political concept to describe the consent of Heaven (complementing

the more personified supreme deity Shangdi of the Shang) to the actions of a

ruler. This consent was the basis of his power; having lost the mandate to rule,

power could be transferred to a successor. Natural desasters were thought to

indicate heavenly dissent which resulted in a change of rule.

In addition peasant rebellions that led to a change in rule were later interpreted as 'sent by heaven': historical events were seen as the manifestation of a divine will. One of these rebellions is connected with the first accountable date of Chinese history, - the year 841 BCE when the tyrannical king Li was driven out of his domaine during a large uprising.

The begin of Zhou rule

When the Zhou dynasty began its rule the first measure was a (re-)distribution of land which considered not only Zhou aristocrats but included members of the Shang royal clan as well as former vassals of the Shang - a strategic measure to secure political stability under the new rule. 71 territories of enfeoffment were created, 53 of which were distributed to Zhou clans [according to the philosopher Xunzi who reports about this early stage of Zhou 'feudalism'], while the rest were endowed upon Shang clan members of the royal family and former followers.

Moving the capital from Zongzhou to Luoyi

The government was characterized by a bureaucracy that was

headed by aristocrats and a set of rituals that concentrated on the ancestral

cult in the royal domaine of the Zhou.

The government was headed by the king who was assisted by an official heading

a staff of ministers who all held the position of dukes and owned respective

domaines of land. There was a minister for the administration of the entire

Zhou territory, a minister for the land and the farmers, a minister of war,

a minister of public works, and a minister of justice.

Different from the Shang the Zhou favored a patriarchal clan system that transmitted power from the father to the son which included the inheritance of land -and the farmers working it- in the feudal states. The feudal lords promised loyalty to the king and sent local products as tributary gifts to the royal domaine which represented a kind of tax income for the king.

The rituals assoiated with government included divination - just as in the Shang. But more prominent than the 'oracle'-bone divination became the divination with yarrow stalks. Notes on this divinatory process with these stalks resulted in the Classic of Changes, the Yijing.

A more acessible source for Zhou history is the classic Book of Songs (Shijing), a compilation attributed to Confucius who reduced the numer of songs included in the collection from originally 3,000 to 306 songs. The songs report about the obligation of the landlord to care for his farmers and of the delivery of goods produced by the farmers and their wives to their landlords. Other songs tell of the works related to sericulture that was in the hands of the women. While the majority of the songs are love songs or songs grieving about a lost love, there is also a famous text that renders the opposition of farmers against an exploitative landlord:

Big rat, big rat,

Do not gobble our millet!

Three years we have slaved for you,

Yet you take no notice of us.

At last we are going to leave you,

And go to that happy land.

Happy land, happy land

Where we shall have our place. (Tanslation by Bernhard Karlgren)

Five severe main punishments were used by the Zhou to maintain order: Marking the face by burning (or tattoos), cutting off the nose, amputating the feet and lower legs, castration, and decapitation. The punishments were not applicable to aristocrats; other culprits who owned enough valuables could buy freedom of punishment.

Zhou bronze inscriptions

Inscriptions in Zhou bronzes tend to be much more elaborate than in

Shang vessels and allow the reconstruction of clan connections

because they praise the accomplishments of their owners. In formulaic language

the inscriptions document the ownership and wishes concerning their lasting

use by the future male offspring in the sacrificial offerings of the clan.

Western Zhou bronze lidded container

Western Zhou fanglei container

The end of the Western Zhou

As time went by and especially after the tyrannical king Li was removed,

power within the central royal domain deteriorated and the feudal lords gained

influence instead. Feudal states attacted the Zhou capital. The Zhou formed

an alliance with and the neighboring Rong who simply stayed in the Zhou territory

instead of leaving after they had accomplished their supportive task. Therefore

the Zhou moved their capital east - close to modern Luoyang in Henan province.

This territory did not belong to the main territory of the Zhou state but was

located in the feudal state of Zheng - a situation that created a severe dependance

of the Zhou from the state of Zheng.

The Eastern Zhou

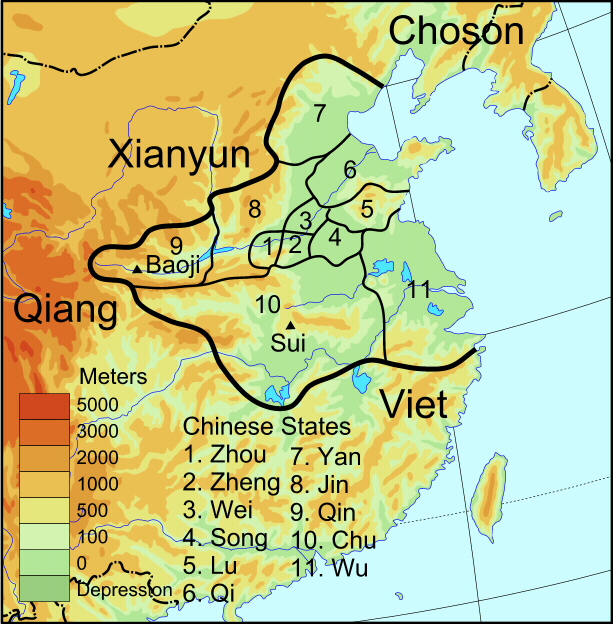

States of the Eastern Zhou (Warring States period)

Bronze bell of the Eastern Zhou

The name 'Chunqiu', Spring- and Autumn period refers to the title of a chronicle of the state of Lu, a rather dry account of events without much literary value. But the fact that the ruler of Lu had commissioned such a chronicle is sensational in itself, since only the Zhou king was allowed to give the order to compose historiographical writings. Two commentators have therefore later written remarks about this 'Timeline of Lu', one titled 'Gongyang Commentary', the other 'Guliang Commentary', and finally a third author ventured to write his own history of the state of Lu, which used the 'Timeline' as its basic sceleton of facts, the Tradition of Master Zuo (Zuozhuan). His name was Zuoqiu Ming, and he may have been a disciple of Confucius. Whoever the author may have been, this work gives a much more detailed account of the events in Lu than the 'Timeline'. Master Zuo also gives an account of the amount of battles fought during this time and describes the alliances between the states.

From the Westen Zhou to the Eastern Zhou the number of feudal states were reduced from 1800 to ca. 100, only one douzen of which had some political relevance. By 221 BCE only one state was left: the state of Qin headed by the feudal lord who unified the country and should become the first emperor of imperial China.

The old political order collapsed during the Eastern Zhou and the focus of power alternated between several states. Therefore the states attempted to form alliances (reinforced by blood convenants) and appointed a lord protector or alliance chief who ruled under the Zhou king. The most important of these leading feudal lords was Chonger [="Double Ear"], the Duke of Jin (r. 636-628). He, who came to power only in old age, was praised by the famous Han historiographer, Sima Qian as a just ruler who re-established order.

When Chonger died a new era of warfare began: the four-horse-chariot warfare with few accompanying footsoldiers in which the aristocrats led the battles was replaced by large infantries of up to 10,000 foot soldiers who were recruited from the farmers working the land during periods of peace. Cast iron was used for reinforcing agricultural tools and weapons as well. And finally a cavalry developed following the model of the 'barbarian' neighbors. One consequence of these large armies were of course huge numbers of victims. The dead and the injured became countless, battle reports state numbers of 60,000, 80,000, or 450,000 dead soldiers.

The swallowing of many small feudal states by the few domiant ones brought a concentration of power in these few states that sent the majority of aristocrats from submissive states into a spin of social downward mobility. This trend was enhanced by the egalitarian practices in the new armies. Good fighters became generals, independent from their social roots. Some of the jobless, well educated and erudite aristocrats became teachers, instrucors and advisors to the rulers. Within this group we find some of the most important philosophers of all times.