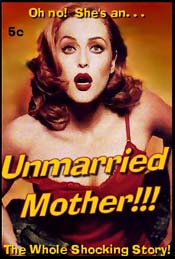

“Out of innocent confusion...

was born heartbreak!” These graphics advertized a 1949 film,

“Not Wanted,” directed and produced by Hollywood star

Ida Lupino. The tragic story featured Sally Forrest (as the unmarried

mother) and Keefe Brasselle. Compare this image to the satirical

image below, which shows a character from the recent TV drama,

“The X-Files.” The contrast illustrates how dramatically

attitudes toward illegitimacy have changed in recent decades.

Before the 1960s, out-of-wedlock pregnancy was such a stigmatized

subject that no one would have poked fun at it in this way. Unmarried

mothers actually were shocking.

|

|

Illegitimacy is not a widely used

word today, and young people may not even recognize it as an insult.

The term designated unmarried mothers, unmarried fathers, and their

unlucky children as deviants. All were called “illegitimate,”

and illegitimate children were sometimes also called “bastards.”

As a label, illegitimacy described their collective status as outcasts

who were legally and socially inferior to members of legitimate

families headed by married couples. Unmarried birth

parents and children suffered penalties ranging from confinement

in isolated maternity homes and dangerous baby

farms to parental rejection and community disapproval. Before

the 1960s, unmarried mothers were usually considered undeserving

of the public benefits offered to impoverished widows and deserted

wives. They were generally denied mothers’ pensions, which

virtually all states granted beginning in 1910, and Aid to Dependent

Children, a federal program created by the Social Security Act of

1935. (Divorced women and non-white women were also excluded.) To

be illegitimate was to be shamed and shunned.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the belief that

children born out of wedlock posed significant social and public

health problems was widespread. The U.S.

Children’s Bureau, for example, devoted a great deal of

attention during its early years to combating infant mortality,

and its research and programs in this area focused disproportionately

on illegitimate children and their mothers. Why? These children

were at higher risk than their legitimate counterparts for malnutrition,

mediocre child care, maternal separation, and other hazards. Unmarried

mothers were, by definition, unattached to male breadwinners and

wage work was their only option for economic survival. The unskilled

occupations in which they were concentrated, such as domestic service

and wet-nursing, ironically required them to care for others’

children but made it very difficult for them to raise their own.

Unmarried women and children may have been tainted with sexual immorality,

but those who lived under the shadow of illegitimacy were endangered.

They needed help, according to reformers and policy-makers, who

insisted that alleviating the stigma associated with illegitimate

birth status would do more to improve child

welfare and family life than either contempt or condemnation.

Eugenicists were also dismayed by illegitimacy

because they considered it a major factor in the reproduction of

mental deficiency, disease, and anti-social behavior. According

to their view, “feeble-minded”

children were more likely to be born to unmarried women because

illegitimate pregnancies were byproducts of retardation, insanity,

epilepsy, or other mental defects. It is not surprising, therefore,

that many native-born Americans of European heritage worried that

their own decreasing fertility rates forecast “race suicide”

and viewed child-bearing in other social groups with alarm. New

immigrants, African-Americans, and members of impoverished rural

white communities were implicated in the scandal of illegitimate

births. The fact that poor and minority communities sometimes displayed

greater acceptance of unmarried mothers was sometimes cited as a

reason to deny children in these communities adoption services.

In the case of African-American children,

perceptions of cultural difference in regard to illegitimacy were

compounded by patterns of legal segregation that impacted child

welfare as surely as they did education, housing, employment,

and voting.

The fact that illegitimate white children might be placed for adoption

casually, with barely any regulation or oversight, worried child

welfare reformers during the early twentieth century. Statistical

studies have recently shown that a majority of birth

parents before 1940 were married—which suggests that poverty,

desertion, illness, and other family crises may have been as significant

as illegitimacy in leading to surrender and placement. But many

adopters preferred illegitimate babies and toddlers and went out

of their way to obtain them. They believed that the dishonorable

origins of illegitimate children made it less likely that natal

relatives would ever come back to claim them or interfere in their

lives. Such views led to the charge early in the century that adoption

encouraged illegitimacy. Surrender, critics insisted, allowed unmarried

men and women to avoid the consequences of sexual indulgence: permanent

responsibility for raising and supporting the children they conceived.

But the desperation of many unmarried mothers was impossible to

ignore, and it inspired a curious combination of sympathy and scrutiny.

Reformers who set out to professionalize child

welfare services did not think that adoption was the answer

to illegitimacy. They believed that preserving natal families was

better, even when those families were incomplete, female-headed,

and burdened by disgrace. They promoted state laws, such as the

one passed in Maryland in 1916, which required women to nurse their

babies and prohibited infant placements for a period of six months.

This kind of regulation limited the choices available to unmarried

mothers deliberately. The point was not only to choke off the adoption

black market and reduce other risks involved in placing illegitimate

infants, but to insure that the recipients of public protection

were subjected to moral discipline and behavioral control. The authors

of such laws believed the state’s first priority was to protect

the most vulnerable victims, and illegitimate babies were more vulnerable

than their mothers, even when those mothers were vulnerable to sexual

victimization.

Attitudes changed sharply during and after World War II. The war

years brought increases in illegitimacy, including among married

women whose pregnancies occurred while their husbands were stationed

far away for periods exceeding nine months. After 1945, illegitimacy

was reinterpreted as a sign of individual maladjustment and psychological

disorder, and adoption consequently appeared a positive solution

for many children. Freudian

developmental theory contributed to this transition. Psychoanalysis

reached the peak of its popularity after 1945, sexualizing childhood

and adolescence while stressing the influence of unconscious sexual

desires throughout the entire life course. Earlier in the century,

figures such as Marion Kenworthy, Jessie

Taft, and Viola Bernard

had encouraged social workers, psychiatrists, and other helping

professionals to consider nonmarital pregnancies as expressions

of neurosis. Girls and women who had sex before or outside of marriage

got pregnant on purpose, whether they knew it or not, according

to the Freudian worldview.

As a pathological and invariably unsuccessful attempt to resolve

emotional problems in dysfunctional families of origin, illegitimacy

became the property of psychology and science rather than morality

and religion. By 1950, women could no longer rely on sexual purity

and difference from men as the foundations of their claims to virtue.

It became much harder for women to claim innocence in cases of illegitimate

pregnancy, and that made it much easier to view adoption as a good

thing.

Demographic and cultural trends evident by midcentury also lessened

resistance to separating babies from their unmarried mothers and

boosted the reputation of early adoption. Unmarried mothers after

midcentury were more likely to be white, middle-class adolescents,

and their mortified families were determined to give these wayward

daughters a second chance to find normal love and maternity through

marriage. In the post-Nazi era, the nature-nurture debate swung

decisively toward nurture, and one result was that eugenic anxieties

about the perils of adopting illegitimate infants moved underground.

After the exterminationist regime of National Socialism, which featured

not only death camps but an ambitious sterilization program for

the biologically unfit, talk about defective children and mothers

had such abhorent implications that it became unmentionable, if

not entirely unthinkable. Instead of making them unadoptable, mental

and physical disabilities gave children special

needs. In theory, they qualified for family life even if they

were still unwanted in practice.

Adoption professionals, who had worked so hard to keep natal families

together just a few decades earlier, changed their minds about family

preservation. Between 1940 and 1970, they acted on the belief that

placing children with married, infertile

couples would save them from doomed lives with unmarried, emotionally

unstable mothers who could not offer them real love or security.

Matching practices during this period,

along with confidentiality and sealed

records, reflected the hope that adoption might completely substitute

one family for another, as if from scratch, severing forever the

embarrassing ties between adoptees and their unmarried birth

parents.

All of this changed again after the sexual revolution of the 1950s

and 1960s, and after Roe v. Wade legalized abortion in

1973. During the past three decades, the stigma associated with

out-of-wedlock births—and nonmarital sexuality in general—has

decreased dramatically. Teen pregnancy still causes periodic panic,

but even very young mothers and their babies are no longer ridiculed

as “illegitimates.”

That the meanings of illegitimacy and adoption could undergo such

drastic change suggests a broader revolution in modern American

thought and culture. During the second half of the twentieth century,

fixed and singular standards of conduct gave way under the pressure

of social and intellectual movements that championed pluralism and

diversity. In an age of civil rights, democracy required new tolerance

for a wide spectrum of values. In spite of the powerful resurgence

of religious fundamentalism and social conservatism in public life

since the 1960s, there is no longer “one right way”

to live, love, or bring families into being in the United States. |