Perhaps the most obvious aspect of any language is its sound structure, known by linguists as its PHONOLOGY (phon = 'sound'; ology = 'study of'). Nilotic languages have completely distinct sound systems from Swahili (a Bantu language, ultimately connected to the Niger-Congo family), and from all Indo-European languages. Thus, writing systems developed to represent the sounds of Latin or Swahili do not always fare so well in representing Nilotic words. Three salient aspects of the Maa sound system are its consonants, its vowels, and its tone.

Consonants

The Maa language has about 25 consonant sounds, written as p, b, t, d, k, g, mb, nd, nj, ng, s, sh, c, j, m, n, ny, ŋ, l, r, rr, y, yy (yi), w, and ww (wu). Dialects may differ in what consonant sounds they have. Thus, Barbara Levergood (1987) describes Arusa Maa as lacking c and p; but instead having voiceless and voiced bilabial fricatives (sounds which are made by blowing through the lips almost as if one were saying p or b).

One must be careful not to assume that letters on paper necessarily represent the same sounds for all languages. The Maa sounds written as b, d, j, g, mb, nd, nj, and ng are IMPLOSIVE, meaning that they are pronounced while the speaker draws air into the mouth. All the others are EXPLOSIVE, meaning that air travels out of the mouth while the sound is made. (By far, most language sounds around the world are explosive). For Maa, explosive sounds include those written as p, t, c, k, though to speakers of other languages, when these sounds occur after a nasal sound or between two vowels, one might be tempted to "hear" them like English 'b", "d", "j" and "g," thus perhaps mis-writing en-gitojó for 'hare' (instead of correct en-kitojó; IlWuasinkishu en-kitejó).

The sound written as ŋ, as in eŋûês 'wild animal,' corresponds to the sound written as ng' in Swahili or ng in English singer (but not the ng of English finger, nor to the sound written as ng in Swahili). The rr is produced by trilling the tip of the tongue against the top of the mouth (like the rr of Spanish).

What are represented as ww (often

represented by wu in practical writing) and yy (yi) can be

described phonetically as "strong" or "fortis", more tightly-articulated

versions of the more gently-articulated sounds w and y.

In Maa, these are clearly distinct sounds, which native speakers use to

distinguish words. Compare:

| éyyáya (éyíáya) | 'He/she will go searching (for something)' |

| éyá | 'He/she will take it' |

| éwwáp (éwúáp) | 'He/she will snatch it' |

| éwál | 'He/she will reply.' |

Vowels

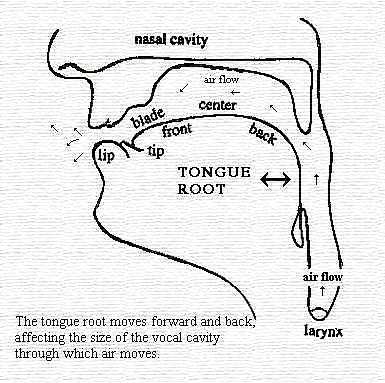

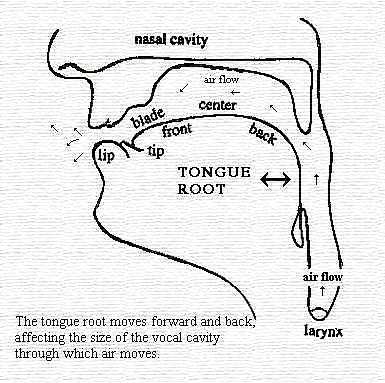

Maa has nine distinct vowels. (For some comparison,

Swahili and Spanish have only 5; while English arguably has 13.) The Maa

vowels divide into two sets, depending on whether the tongue root is moved

forward (enlarging the throat cavity); or is in a neutral position or moved

backwards (reducing the throat cavity). The size of the throat cavity affects

the acoustic sound waves that travel through the air, making the sounds

distinct as they are first perceived by the hearer's ear, and then interpreted

by the brain. When the tongue root is moved forward, this is referred to

as Advanced Tongue Root (+ATR; which Tucker and Mpaayei called "close");

when the tongue root is in a neutral or retracted position, the sound is

referred to as Non-advanced or Retracted Tongue Root (-ATR; which Tucker

and Mpaayei called "open") (Figure 3). There is simply nothing like this

distinction in Swahili or Indo-European languages, and it requires considerable

practice for someone whose first language does not have such sound contrasts

to learn to reliably recognize, and produce, the difference.

Many Maa words differ from each other just by a change in the

ATR value of a vowel. Thus, it is important to represent all nine vowels,

which we do here as follows:

| ADVANCED TONGUE ROOT | i | e | o | u |

| NON-ADVANCED TONGUE ROOT | ɪ | ɛ | ɔ | ʊ |

| NEUTRAL (also non-advanced) | a |

With these nine symbols, the fact that the following words sound different

can be represented:

| érík | 'He/she will lead it.' |

| ɛ́rɪ́k | 'He/she will nauseate (someone).' |

| épét | 'He/she will plaster it.' |

| ɛ́pɛ́t | 'He/she will keep close to it.' |

| éból | 'He/she will open it.' |

| ɛ́bɔ́l | 'He/she will hold it (by the mouth).' |

| ébúl | 'He/she will pierce it.' |

| ɛ́bʊ́l | 'He/she will prosper. ' |

To find out more about how these contrasting vowels sound, click here.

Tone

A third, extremely important, feature of Maa is its tone. The meaning of individual Maa words can be changed just by changing the tone (or pitch, i.e., relative acoustic frequencies) on which different syllables are pronounced.

From a linguistic perspective, Maa has two

"basic" tones, High and Low. But these can be combined so that some words

end with a tone that moves quickly from High to Low and hence is perceived

as Falling. Also, when listening to words in natural context, more than

two acoustic pitches can be perceived because the tones are affected by

surrounding tone contexts and by the general intonational patterns in sentences

and discourse. In this description, the basic tone patterns are written

over vowels as High á and a (word-final), Low a

and à (word-final), and Falling â. Much humor,

if not much misunderstanding, can arise if the tones across a word are

inadvertently changed. The tone is particularly important in the grammar;

a bit of this can be appreciated by considering the following simple pairs:

| áadôl | 'He/she/they will see me.' |

áádól

|

'I

will see you (singular).'

|

| kɪ́ntɔ́nyɔrra | 'You (singular) have made me love it. |

| kɪ́ntɔ́nyɔ́rrâ

|

'You (plural) have made

me love it.'

|

| ɛ́ár ɔlmʊrraní ɔlŋátúny | 'The warrior will kill the lion.' |

| ɛ́ár ɔlmʊ́rránì ɔlŋatúny | 'The lion will kill the warrior.' |

Back to top

Back

to The Maasai Language

This page written by Doris L. Payne